“If countries in the region used to view Afghanistan as a troublemaker of sorts, then lately the public and expert discourse has been focused on finding the weakest link in Central Asia itself. It is hard to be a good neighbor in a bad neighborhood”, – Anna Gusarova, an expert from the Kazakhstan Institute for Strategic Studies (KazISS), analyzes the challenges and threats in the region in this cabar.asia exclusive.

Follow us on LinkedIn!

The Central Asian expert community has traditionally focused on two approaches to analyzing security challenges and threats. The first approach links the region to Afghanistan and the risks it presents, including the consequences of the withdrawal of American forces. The second approach concentrates on geopolitical turbulence caused by players outside of the region such as Russia, the European Union, the United States, the People’s Republic of China, etc.

However, it must be noted that the system for perceiving security risks and threats varies greatly among the Central Asian states due to their individual national interests. Multiparty cooperation and dialogue on the most sensitive issues and points of contact is made noticeably more difficult due to this.

Kazakhstan has traditionally viewed the region as one priority of many in its multi-vector foreign policy strategy. The official Kazakhstani Foreign Policy Concept for 2014 – 2020 pays particular interest to the politically stable, economically sustainable, and safe development of Central Asia.[i] The main objectives of Astana’s multi-vector foreign policy in Central Asia are ensuring regional security and building mutually beneficial intraregional cooperation.

Additionally, the Concept sets out the official position of the Republic of Kazakhstan regarding the situation in Afghanistan, which boils down to the following three forms of cooperation:

- Supporting the common efforts of the international community towards the national reconciliation and political settlement in Afghanistan.

- Eliminating threats to regional and global security.

- Participating in the socio-economic development of Afghanistan.[ii]

Astana’s Shuttle Diplomacy

In the Afghan case, Astana actively takes on the role of peacekeeper and intermediary. This is particularly relevant within the framework of rapprochement and cooperation between the countries of Central Asia. At the moment, these states are not prepared for this level of cooperation and continue to view Afghanistan as a source of terrorism, extremism and drug trafficking as opposed to a partner in the spheres of trade, economics, energy and security.

It is obvious that the Afghan government is in need of support from the international community. Therefore, at this stage Kazakhstani diplomatic efforts are mainly aimed at the inclusion of Afghanistan in political dialogues through regional and international organizations as well as multilateral development institutions such as the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA), the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the Central Asian Regional Information and Coordination Centre for Combating the Illicit Trafficking of Narcotic Drugs, Psychotropic Substances and Their Precursors (CARICC), the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), the Asian Development Bank (ADB), and the Istanbul Process.

As a member of the working group on cooperation and coordination of the CSTO and SCO efforts regarding Afghanistan, Kazakhstan has assiduously attempted to renew the activities of these groups, which has led to Afghanistan receiving SCO observer state status.

With an increase in Taliban and ISIS activity in Afghanistan, the challenges and risks for regional security stemming from the spread of violent extremism, terrorism and drug trafficking require that the political leadership of Central Asia undertake collective measures to counter these threats. Therefore, Kazakhstani Foreign Minister Erlan Idrisov’s recommendation at the SCO Summit in Ufa to resume the SCO – Afghanistan contact group has become particularly relevant.[iii]

Kazakhstan’s security is obviously not as strongly dependent on or correlated with the withdrawal of forces from Afghanistan. That being said, the security of Central Asia as a whole is significantly impacted by what happens in Afghanistan. The recent gains of the Taliban in Kunduz, the Haqqani network in Kabul and Khost Province, as well as ISIS affiliates in Nangarhar Province along the Pakistani border show that the situation in Afghanistan is worsening. Some American experts and former Pentagon officials are of the opinion that military operations in Afghanistan in 2015 were at levels of intensity and brutality not seen in years.

Taking into consideration ISIS’s increasingly strong foothold in Afghanistan, building a regional dialogue on combating violent extremism and terrorism in the short-term can become one of the foundational aspects of Central Asian dialogue. In any case, the Afghanistan factor will remain on the agenda of each country to a greater or lesser degree.

Kabul and Astana: What is Next?

In the 13 years since the opening of the Kazakhstani embassy in Kabul, Kazakh-Afghan relations have undergone a number of changes. The 2000’s era approach of aid provision has given way to the building of a dialogue on trade and humanitarian issues.

Additionally, the dynamics of the developing relationship is poorly presented in the media and expert discourse. The Afghan issue is often limited to news stories that briefly characterize bilateral relations. In the analytical community, the problems of Afghanistan and its impact on national and regional security have been to a large degree mythologized.

On one hand, Astana has sought to build a deeper relationship with Kabul, which could be viewed as preventive measures if viewed from a security conscious point-of-view. On the other hand, Kazakhstan has continued its tradition of calling for necessary international support for Afghanistan at all major international forums and meetings.

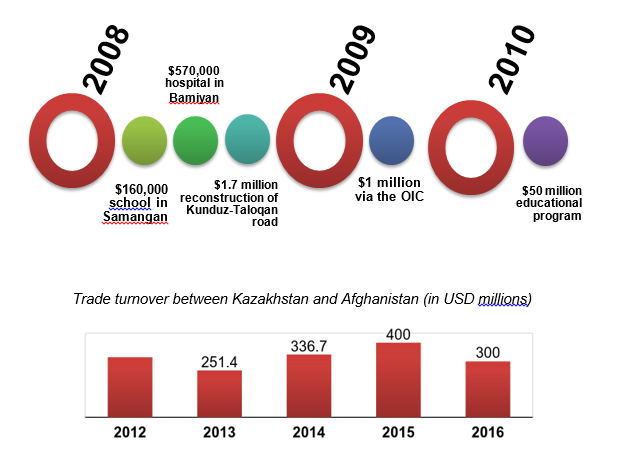

Kazakhstan has been implementing its Special Plan of Action for Assisting Afghanistan since 2007.[iv] In 2008, Kazakhstan built a school in Samangan Province, a hospital in Bamiyan Province, as well as undertook the reconstruction of the Kunduz-Taloqan road ($2.38 million). In 2009, Kazakhstan provided $1 million to the OIC’s Trust Fund for the Reconstruction of Afghanistan, and Kazakhstan is 6 years into a 10-year, $50 million educational program[v] for Afghan students in Kazakhstani universities.[vi] In 2014, Kazakhstan provided humanitarian aid to Afghanistan worth $3 million.[vii]

Figure 1. Kazakh-Afghan Cooperation in Numbers

Trade turnover between Kazakhstan and Afghanistan (in USD millions)

With regards to economic cooperation, there are arrangements for its activation on the political level. In 2015 trade turnover between Kazakhstan and Afghanistan reached $400 million, which is significantly higher than the indicators of the past 3 years. Over the course of the first 6 months of this year, the trade turnover has already hit $300 million, though the lion’s share of this trade is Kazakhstani exports.

In January 2016, the Afghan government lowered tariffs on customs duties for Kazakhstani wheat by 5%, and Kazakhstan has adopted measures to lower railroad tariffs for the delivery of grain and flour.[viii]

Currently, there is a common interest in deepening trade ties and economic cooperation. Kazakhstan is particularly interested in the Afghan market and transit to the Indian Ocean, and the export of Kazakhstani raw materials and products is of particular importance for Afghanistan.

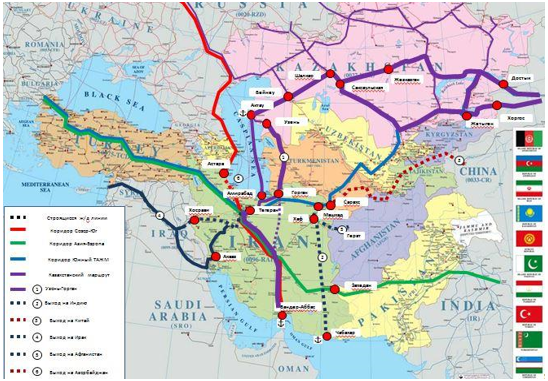

Participation in the projects under the banner of the New Silk Road are being undertaken in the shadow of the Russian economic crisis and its negative impact on the ruble-dependent Central Asian economies. In particular, entering the southern market (Iran, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan) is viewed as an option to further develop the transportation and economic connections between the Central Asian states and states of South Asia.

Figure 2: Kazakhstan’s prospective southern routes

Source: http://www.kazlogistics.kz/ru/useful/maps/

Regardless of the unlimited opportunities available by entering the Afghan market, security continues to be viewed as the main obstacle for closer ties with the Central Asian states.

C5+1: A Win-Win Strategy?

For the past 10 years, the American expert community has been dominated by the theory that improving the regional economic situation is best undertaken by means of a regional dialogue to solve regional problems in particular those involving hydroelectric power, border issues, and transportation. Obviously, the US will continue to undertake efforts to build the economic potential of an attractive Central Asian ‘integrational core’ for Afghanistan.

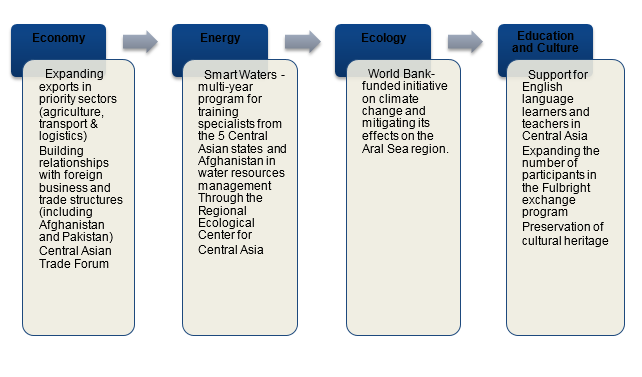

Over the course of the past 25 years, the Central Asian expert community has long articulated the need to launch regular, high-level political dialogue. On one hand, the C5+1 format strengthens the integrity and unity of Central Asia and as well as its recognition by outside players. On the other hand, this reboot of American regional policy is associated with greater multi-channel cooperation within a framework of strengthening regional integrity and closer ties with Afghanistan. At the same time, a Central Asian dialogue would need to promote gradual solutions to existing sensitive issues. It should be noted that the program does not involve new breakthrough approaches, projects, investments, or sectors of cooperation between the US and the Central Asian states. Meanwhile, the American programs involving energy and trade will be directed at developing the region’s connections with Afghanistan and Pakistan. The ecological dimension maintains a special role in the spectrum of regional projects.

The American strategy in Central Asia via the C5+1 format is aimed at developing a shared vision and understanding of Afghanistan on the part of Central Asia as well as Afghanistan’s inclusion in various spheres of social life in the region.

Figure 3. The United States’ Program in Central Asia (until 2020)

Considering the region’s preference for strategic partnerships with external players as well as the extremely low level of cooperation between the Central Asian states let alone with Kabul, Washington’s bet on this format allows for a common reference point. Cooperation in the areas of countering violent extremism and terrorism will play important roles in the American strategy in Central Asia.

The Contours of Central Asian Security

In speaking of Central Asian perspectives in the area of security, it is important to recognize the cross-border challenges and threats. Regardless of the seemingly different systems for assessing risks, increasing securitization is a trend that is visible in every country in the region.

Ultimately, cooperation in solving Central Asian security problems must be undertaken pragmatically and in an economically feasible manner. In the face of modern global economic trends and geopolitical turbulence, it is extremely important to consolidate efforts to meet security challenges of the past, present and future.

In evaluating the prospects for future cooperation, there is a dire need to understand the idiosyncrasies of the region in order to collectively combat violent extremism and terrorism. One of the possible collective mechanisms could be regional simulations on combatting foreign fighters. These types of activities could allow for the exchange of experience as well as the development of a system for combatting radicalization and intercepting foreign fighters in crisis-prone regions.

In the end, the issue of violent extremism and terrorism unites all Central Asian countries. The fight against these challenges and threats requires the government to establish cooperation in many fields, including law enforcement agencies, the liberalization of trade and visa policies, data exchange, etc.

The political will to engage in dialogue with neighbors on level of governmental-level, people-to-people diplomacy, and research projects aimed at studying the region would allow for an increase in the level of interest Central Asian states have in each other.

If countries in the region used to view Afghanistan as a troublemaker of sorts, then lately the public and expert discourse has been focused on finding the weakest link in Central Asia itself. It is hard to be a good neighbor in a bad neighborhood. From time to time, various countries in the region have been viewed this way: Turkmenistan with prognoses of another “colored” revolution, Tajikistan due to its proximity to Afghanistan, and Kyrgyzstan as simultaneously the most unstable and democratic state in the region. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan differ in their multi-vectored approach, openness, independence, and to some extent their neutrality.

However, regardless of the centrifugal forces, the “prisoner’s dilemma” of Central Asia, that have existed since the region was granted independence, it is necessary for the states to start a centripetal process within the region. In the case of Central Asia, it is obvious that cooperation, collaboration, or integration, particularly in the areas related to the economy, hydropower and transportation, is possible only through dialogue.

References:

[i]“Foreign Policy Concept for 2014 – 2020, Republic of Kazakhstan.” Kazakhstani Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 9 May 2014. http://mfa.gov.kz/index.php/en/foreign-policy/foreign-policy-concept-for-2014-2020-republic-of-kazakhstan

[ii] ibid

[iii] Sokolai, O. “Instability in Afghanistan and the Activities of the ‘Islamic State’ are the Key challenges for the SCO (Нестабильность в Афганистане и деятельность «Исламского государства» остаются ключевыми вызовами для ШОС).” vlast.kg. 5 June 2015. https://vlast.kz/politika/11430-nestabilnost-v-afganistane-i-deatelnost-islamskogo-gosudarstva-ostautsa-klucevymi-vyzovami-dla-sos.html

[iv] “President Nazarbayev’s speech at the Conference of Foreign Ministers of Istanbul Process Participating States (Выступление Президента Казахстана Н.А.Назарбаева на конференции министров иностранных дел стран-участниц Стамбульского процесса).” 26 April 2013. http://www.akorda.kz/ru/speeches/external_political_affairs/ext_speeches_and_addresses/page_213696_vystuplenie-prezidenta-kazakhstana-n-a-nazarbaeva-na-konferentsii-ministrov-inostrannykh-del-stran-uch

[v] Lebedeva, M. “Kazakhstan. Especially for Afghanistan (Казахстан. Специально для Афганистана).” zakon.kz. 30 September 2015. http://www.zakon.kz/4745842-kazakhstan.-specialno-dlja-afganistana.html

[vi] Kazakhstan has already provided 4,000 Afghan students with free education as a part of this program.

[vii] Kaumetova, I. “Kazakhstan-Afghanistan trade turnover amounts to about $ 300 mln.” Kazakhstan 2050. 20 April 2015. https://strategy2050.kz/en/news/34263/

[viii] “Ambassador: The Afghan market is interesting to Kazakhstani businessmen (Посол: Афганский рынок интересен казахстанским бизнесменам).” express-k.kz. 20 April 2016. http://www.express-k.kz/news/?ELEMENT_ID=72030

Author: Anna Gusarova, expert KazISS (Astana, Kazakhstan)

The views of the author may not coincide with the position of cabar.asia