“The paradox of relations between upstream and downstream countries is that the most reliable way to obtain guarantees that upstream Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan will not block the flow of water to downstream countries is to buy the electricity that they produce. Kazakhstan often avails itself of this approach and there is no reason Uzbekistan should not do the same. But for that to happen the Uzbek authorities should reconsider their isolationist stance towards relationships with neighbors,” writes senior researcher at the Eurasian Research Institute, Farhod Aminzhonov, exclusively for cabar.asia.

Follow us on LinkedIn!

The water-energy nexus has for many years been a source of conflict between upstream countries Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, with their significant hydropower projects, and downstream countries, especially Uzbekistan, whose agriculture is highly dependent on the flow of water from trans-boundary rivers. Upstream states often emphasize that the implementation of hydropower projects is in the best interests of all the region’s countries. Regional hydroelectric power plants (HEPs) including Tajikistan’s Rogun and Kyrgyzstan’s Kambarata-1 were, after all, designed in Tashkent during the Soviet era, by Uzbek engineers among others. However, as practice shows, it has been impossible to influence Uzbek decision-makers on this point, believing as they do that the development of the region’s hydropower potential will automatically mean a reduction in the volume of runoff water from the trans-boundary rivers. This article attempts to consider the external and internal factors shaping the position of the Uzbek authorities in relation to hydropower projects across the region.

The water-energy nexus has for many years been a source of conflict between upstream countries Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, with their significant hydropower projects, and downstream countries, especially Uzbekistan, whose agriculture is highly dependent on the flow of water from trans-boundary rivers. Upstream states often emphasize that the implementation of hydropower projects is in the best interests of all the region’s countries. Regional hydroelectric power plants (HEPs) including Tajikistan’s Rogun and Kyrgyzstan’s Kambarata-1 were, after all, designed in Tashkent during the Soviet era, by Uzbek engineers among others. However, as practice shows, it has been impossible to influence Uzbek decision-makers on this point, believing as they do that the development of the region’s hydropower potential will automatically mean a reduction in the volume of runoff water from the trans-boundary rivers. This article attempts to consider the external and internal factors shaping the position of the Uzbek authorities in relation to hydropower projects across the region.

Central Asia’s Unified Energy System (CAPS) and independent systems

Central Asia’s United Energy System (CAPS) was established in the 1960s and 1970s. The system was made up of contributions by both hydropower facilities in the upstream countries (30%) and thermal power plants (TPPs) in the downstream countries. CAPS, also known as the Central Asian “power ring” connects 83 stations in Southern Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and most importantly Uzbekistan.[i] Under this system, Uzbekistan had a key role. Firstly, the system was regulated by the coordination control center “Energia”, based in Tashkent. Secondly, 51% of its generating capacity was allocated to Uzbekistan, 13.8% to Kyrgyzstan, 9.1% to Kazakhstan and 15% and 10% to Tajikistan and Turkmenistan respectively.[ii] Thirdly, power lines linking these countries were designed based on rational use and transportation of electricity. The most logical routes were through Uzbekistan, transforming it into a sort of hub for CAPS.

The resource sharing mechanism ensured a stable and reliable supply of electricity to the Central Asian countries. The mechanism was quite simple: Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan ensured the flow of water during the growing season, while exporting hydropower to countries in the downstream. Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan supplied petroleum products, gas and thermal energy to the upstream countries in exchange. When Turkmenistan withdrew from the system in 2003, little change was felt. But with the exit of Uzbekistan in 2009 CAPS collapsed.[iii]

After the collapse of the Union, all countries, to varying degrees, pursued policies aimed at the creation of independent energy systems that were less vulnerable to unilateral reductions on the part of newly independent suppliers. Thus, ensuring energy security within the CAPS framework proved harder every year. Aiming to create independent systems, the countries in the region gradually achieved more autonomy/isolation in terms of power transmission. But systems can only be truly considered independent if volumes of electricity supplied to the domestic market by national production cover the needs of that country. Apart from Turkmenistan and, to some extent Kazakhstan, none of the other countries in the region boast independent energy systems.

Main reasons for the collapse of CAPS

Approximately 80% of the region’s water is formed on the territory of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, while 85% is consumed by Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and most significantly, Uzbekistan. Quotas for the use of trans-boundary rivers have Uzbekistan receiving some half of the region’s water, which is sufficient for its needs. Given Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are physically not able to consume the amount of water they receive under the quota, the downstream countries actually receive plenty of water. For example, under the current existing quota Tajikistan has the right to use 15.4% of the flow of the Amu Darya water, Uzbekistan 48.2% and Turkmenistan 35.8%. In 2011, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan’s quotas were set at 22 км3, but in practice the two countries used 28.2 km3 and 29.4 km3 respectively.[iv]

Central Asian countries are among the highest water consumers per capita in the world. Uzbekistan, places 4th place after neighbouring Turkmenistan, Iraq and Guyana on this indicator.[v] Such high levels of consumption are driven by the inefficiency of irrigation systems in the region. Of the 90 % of the water consumed in agriculture (in particular through the cultivation of cotton and other crops), 70% does not reach the fields.[vi] However, Uzbekistan cannot afford multi-million dollar projects to implement water-saving technologies and modernize infrastructure. Uzbekistan’s dependence on current volumes of water consumption are one of the main factors determining the country’s policies in relation to hydropower projects in the region.

Thus, if the upstream countries forge ahead with plans to build large hydropower plants (Kambarata – 1 in Kyrgyzstan and Rogun in Tajikistan), they will be able to physically take the water allocated to them under the existing quota, which is at odds with the interests of Uzbekistan. Uzbek authorities believe that if the projects are completed it will be much more difficult, both financially and politically, to solve problems relating to the distribution of water than under the present status quo, since the mega-dams can disrupt the balance of the flow of water.

Limited potential to increase internal production

The total production capacity of electric power plants in Uzbekistan is 12.3 GW, 11 GW of which is produced by thermal power plants, mainly operating on gas. Uzbekistan thus consumes almost as much as gas as it produces.[vii] Given the fact that over the last ten years there have been no discoveries of major new gas fields in the country and no sharp increase in gas production, there is no logic in relying on an increase in production from gas-powered electricity stations. And, while Uzbekistan regularly emphasizes the need to develop alternative energy, renewable energies account for a mere 2% of total production.

Uzbekistan is currently attempting to solve its electricity shortage problems by boosting its hydropower potential. The government has approved a new program to develop the hydropower sector over the period 2016-2020. Under this program some $889.41 million in loans and from the budget will be spent on the modernization of hydropower plants and the construction of new facilities.[viii] The five-year plan involves the implementation of 15 projects, 11 of which are aimed at the modernization of existing facilities, including the largest facilities like Charvak hydropower plant (620 MW) and the Farkhad hydropower plant (126 MW). Charvak HEP, which accounts for half of total electricity production produced by the country’s hydro sector was built over a decade from 1963 to 197. Farkhad HEP was launched even earlier in 1953.[ix]

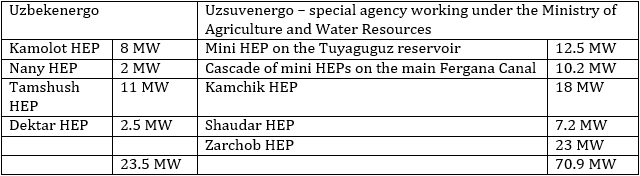

Planned construction of new HEPs during the period from 2016 to 2020[x]

However, these projects appear more like an attempt to maintain existing productive capacities rather than significantly increase them. Upon completion of the implementation of these initiatives it is expected that the electricity production level of national energy company Uzbekenergo will reach 919.9 MW and that of the special agency under the Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources Uzsuvenergo will reach 465 MW.[xi] Considering the fact that present installed hydroelectric capacity is slightly less than 1.3 GW, this is not a significant jump. Uninterrupted supply of energy could instead be ensured by importing clean and relatively cheap electricity from Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. First, however, it is necessary to resolve the conflict of interests in the water and energy sector and begin the process of making concessions.

Hydroelectric projects remain on the agenda

Notwithstanding the disintegration of CAPS, Kyrgyzstan continues to develop export-import relations with Kazakhstan. In the future it will be possible for the country to develop its thermal productive capacities, with the Kara-Keche CHP facility of a capacity of 1400 MW and with a much greater efficiency.[xii] Kyrgyzstan’s level of energy security is low, but the situation in Tajikistan is considerably worse. Therefore, Uzbekistan’s relations with Tajikistan have an important bearing on the hydropower politics in Central Asia as a whole.

Since the energy sector of Tajikistan was linked only with Uzbekistan, Tajikistan faced complete isolation after the collapse of CAPS. Seasonal variations in electricity production mean that neither the population nor industry receive sufficient supplies of energy in the winter periods. Tajik authorities have high hopes for Rogun, which will not only near double installed hydropower production capacity by adding 13 bn. KWh/d of installed hydropower production capacity to the present capacity of 16.5 bln. KWh/d[xiii], but also allow for a significant increase in electricity production in winter.

The importance of the Rogun hydroelectric power station also lies in the fact that without it, Tajikistan will soon lose its main operating HEP, Nurek. Today, Nurek produces 70% of the country’s electricity, and is the only power plant with a large enough reservoir to produce electricity in the winter. “If Tajikistan fails to construct the Rogun hydroelectric power station, it will lose Nurek HEP,” said the head of the national dispatch center at the state electricity company Barki Tojik, Odin Chorshanbiyev. This is because the high level of siltation affecting the Nurek reservoir will deprive it of the possibility of accumulating the water needed to control runoff and ensure winter electricity generation just 20 years from now.[xiv] This is the surest indicator that Tajikistan will not back down from plans to develop the sector, since this is simply a matter of survival for the country. Over time, the necessity of building Rogun will only grow.

Potential to solve the problem of the water-energy nexus

Uzbekistan will have to come to terms with the potential development of Rogun. But given the current situation, it is Tajikistan that will have to make concessions across a range of points. Tajik authorities must look for agreement on the height of the Rogun dam, its annual volume of water intake, the possibility of releasing extra water for Uzbek agriculture in dry years, and so on.

Tajikistan is not able to finish Rogun (estimated cost of $3-6 billion) on its own. Uzbekistan understands that and uses to its advantage. International donors such as the World Bank or the Asian Development Bank cannot fund projects on trans-boundary rivers without the consent of all riparian countries, and exerting pressure on Uzbekistan is quite difficult. However, there are a number of reasons as to why Uzbekistan may, in the near future, reconsider its position in relation to the implementation of hydropower projects in upstream countries:

- Firstly, Uzbekistan is not able to independently provide an uninterrupted and adequate supply of electricity for its population. Opportunities to develop internal generating capacities in the country are few. The fastest and most reliable way of improving electricity delivery in the future is the rational use of resources and a fair trade in electricity. Without exporting large amounts of hydropower, Tajikistan is wasting water. Thermal power plants in Uzbekistan meanwhile produce electricity and feed the central heating system. Due to a lack of imports of hydroelectric power in the summer, Uzbekistan is using one of its most strategic natural resources irrationally, by burning gas for the purpose of generating electricity.

- Climate change has created favourable conditions for the development of hydropower. Over the past few years, warmer winters have provided a volume of water flow higher than in previous years. The more water there is, the more electricity. The water is feeding trans-boundary rivers formed by melting glaciers and snow cover in the mountains. This year, for the first time in the last 60 years the Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan segments of the Syr Darya did not freeze in winter. The danger is that the glaciers are melting at such a pace that in a few decades they will retreat to the point that they no longer replenish the trans-boundary rivers of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya. The irrational use of water in the context of the warming air is not only negatively affecting the ability to produce electricity, but also regulating runoff water for irrigation in downstream countries, chiefly Uzbekistan.

- Uzbekistan has traditionally used the upstream countries’ dependence on Uzbek electricity and gas deliveries as a component of its foreign policy, including as regards its position on water resource use and strategic hydropower projects. However, at present, following the discontinuation of those deliveries, the Uzbek authorities have almost no leverage on the upstream countries other than the possible use of force.

CAPS has collapsed, but interdependence among the region’s countries has remained in place and acknowledging this can substantially improve Uzbekistan’s energy security, as well as that of other countries in the region:

- Infrastructure for transporting electricity with small investments in upgrades will allow for the electricity trade to resume as soon as possible.

- Each of the countries of Central Asia retains a comparative advantage in the development of different kinds of resources: Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan have hydropower, Uzbekistan has gas-powered CHP plants, Kazakhstan has coal-fired CHP plants. These complementary sectors enable optimal resource use at regional level when involved into cross-border trade in electricity.

- Cross-border trade in electricity will solve the problem of seasonal variations in electricity production for the upstream countries, and increase the amount of clean energy in the overall balance of the downstream countries’ consumption.

- Rational use of resources will produce electricity at the lowest cost, which will lower the price and make it more accessible for both internal and external customers.

Recommendations

Developing hydro-electricity and building dams have several aims:

- a) Production of electricity for the domestic market;

- b) Increasing export potential;

- c) Managing water resources.

These goals are not mutually exclusive. However, national policy can differ in terms of the prioritization of these goals. A regulatory mechanism is required.

If Uzbekistan controlled the territory of upstream countries, it is likely that the policies of the Uzbek government in relation to the possible development of hydropower potential through the construction of large hydropower plants like Rogun and Kambarata-1 would be different. The paradox of relations between upstream and downstream countries is that the most reliable way to obtain guarantees that upstream Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan will not block the flow of water to downstream countries is to buy the electricity that they produce. Kazakhstan often avails itself of this approach and there is no reason Uzbekistan should not do the same. But for that to happen the Uzbek authorities should reconsider their isolationist stance towards relationships with neighbours.

After the collapse of CAPS, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan redirected some of the electricity they once traded towards the foreign market of Afghanistan. If capacity allows Tajikistan to supply both the Afghan and Uzbek markets in the summer, then Uzbekistan would be able to supply electricity to Tajikistan in winter merely by reducing its deliveries to Afghanistan. Afghanistan pays Uzbekistan 10 cents per 1 kWh. Therefore, Tajikistan, like Kyrgyzstan, should pay a similar price in order that the cross-border trade in electricity to be revisited. Large hydropower plants allow Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan to produce big amounts of electricity, adding revenues to the budget. In turn, these countries will be able to pay for Uzbek electricity at a competitive price. Most important from Uzbekistan’s point of view is to receive an assurance that the upper reaches of the country will not hold onto more water in order to generate electricity in the winter, which could result in shortages for the downstream state. In order to create an effective mechanism for regulating water and energy issues that can cause conflict, the countries of the region must first enter into a dialogue.

At the moment, there is no effective platform for discussing solutions to the problem of water resources allocation and the utilization of hydropower potential of the region. It is important that any attempt to create such a platform comes from the Central Asian countries themselves with any intervention from intermediaries strictly limited. The World Bank has spent hundreds of millions of dollars on an independent assessment of the environmental, economic and social parameters of Rogun HEP, which took 7 years. As a result, they came to a positive conclusion that in many respects was reminiscent of the one that guided Soviet planners 35 years ago. This assessment, unfortunately, has not won Uzbekistan over to the idea of Rogun, and the Tajik side has struggled to attract investors to complete construction.

All attempts to come to an understanding have been interrupted by the fact that during negotiations the parties speak “different languages”. Uzbekistan blocks the construction of the hydropower plants, emphasizing their catastrophic consequences for Uzbekistan. Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan on the other hand emphasize their sovereign right to use the environmental/water resources of their countries and provide assurances that the construction of dams and water use will comply with international law and be in accordance with the distribution of water resources.[xv] Independent experts concluded in the 2014 final report on Rogun that the most cost-effective version of the project is a dam set at a height of 335 meters with a generating capacity of 2800-3600 MW.[xvi] For the authorities of Tajikistan the project is viewed as the primary source of clean and renewable energy for the country and the region as a whole. Rogun is being constructed in a seismically active area, however. In the event of rupture, the dam could create a wave height of 245-280 meters in the breakout area and 6-7 meters on the territory of the downstream countries. This would expose 5 million people (3 million living in Uzbekistan) to serious threat and destroy 1.3-1.5 million hectares of land through flooding. Thus Uzbekistan views a natural disaster in the Rogun area as having the potential to cause irreparable damage to the country’s agriculture.[xvii]

But the analysis shows that against he background of a deteriorating situation in ensuring sufficient and uninterrupted supplies of electricity in Uzbekistan, the government will be forced to reconsider its position regarding the construction of large hydroelectric facilities in upstream countries in the near future. Internal, rather than external processes should bring the government to the negotiating table and accede to the construction of the Rogun and Kambarata-1 hydroelectric dams. Reintegrating the Central Asian countries on the basis of a single system may not work, but the resumption of mutually beneficial trade relations on a bilateral basis is quite feasible. Short-term trade agreements on electricity supply during peak periods of consumption could be the starting point, with sales concluded on the basis of financial arrangements. But trade agreements that go beyond formal transactions could also come under consideration. It is possible to develop trade in the form of swap agreements and barter wherever mutually advantageous for instance. Experience has shown that attempts to solve water and energy problems through the use of third parties as mediators is likely to fail. Governments themselves need to initiate the dialogue.

References:

[i] Asian Development Bank, Electricity, Final Report RETA 5818 (2000) -11 с.

[ii] ibid.

[iii] Sebastien Peyrouse, Central Asian Power Grid in Danger, CACI Analyst, Сентябрь 2009, http://old.cacianalyst.org/?q=node/5232/print.

[iv] Nariya Khasanova, Revisiting Water Issues in Central Asia: Shifting from Regional Approach to National Solutions, Central Asia Fellowship Papers no. 6, October 2015, – 3 с. https://app.box.com/s/fornzf5490xyou1juaw0.

[v] Olly Varis Resources: Curb Vast Water Use in Central Asia, Nature, October 1, 2014, http://www.nature.com/news/resources-curb-vast-water-use-in-central-asia-1.16017.

[vi] Rakhmatullayev and others, Water Reservoirs, Irrigation and Sedimentation in Central Asia), Environmental Earth Sciences 68, no. 4 (2013).

[vii] Government of the Republic of Uzbekistan, Energy Resources of Uzbekistan, http://www.gov.uz/en/helpinfo/energy/10004.

[viii] Uzbekistan passes a program to develop hydroenergy, Uzdaily.uz, November 23, 2015, http://www.uzdaily.uz/articles-id-26999.htm.

[ix] Venera Radjnaya, HEPs will produce 9.2% of Uzbekistan’s electricity in 2015, Nuz.uz, November 19, 2015, http://nuz.uz/ekonomika-i-finansy/4407-ges-uzbekistana-proizvedut-v-2015-godu-92-elektroenergii.html.

[x] A program to develop hydroelectric power until 2021 is produced.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Joomart Otorbayev, Problems and potential for the development of hydroelectricity in the Kyrgyz Republic, http://www.gov.kg/?p=41665&lang=ru.

[xiii] World Bank, Ecological and social assessment of the impact of the Rogun HEP, Alternative Analysis July 2014, Almaty, Kazakhstan.

[xiv] Asian Development Bank, Pushing for Energy Security and Trade in the Region, Manilla, http://www.carecprogram.org/index.php?page=energy.

[xv] Ekaterina Klimenko, Central Asia as a Regional Security Complex, Central Asia and Caucasus Press 12, no. 4 (2011).

[xvi] Barki Tojik, Technical-economic assessment of the Rogun HEP, World Bank, 2014 http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/eca/central-asia/TEAS_Executive%20Summary_Final_eng.pdf.

[xvii] World Bank, To Executive Secretary, The Inspection Panel, 2010 http://siteresources.worldbank.org/ECAEXT/Resources/258598-1297718522264/Request_for_Inspection_Eng.pdf.

Author: Farkhod Aminzhonov, Ph.D., senior researcher at the Eurasian Research Institute (Kazakhstan, Almaty).

The views of the author may not coincide with the position of cabar.asia