“International ratings of states had become not only an instrument of global governance, but also a key criteria for investment of money and were creating the image of the state in the international arena. Despite the fact that huge funds had been allocated to the republic, the level of wellbeing and incomes changed insignificantly”, – Ainura Akmatalieva, a political analyst, specially for cabar.asia, reveals the peculiarities and the main trends in the foreign policy of Kyrgyzstan.

Follow us on LinkedIn!

The dilemma of Kyrgyzstan’s foreign policy is conditioned by the need to realize its national interests and the search for a strategic certainty in the context of globalization. To date, according to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Republic has established diplomatic relations with 135 countries of the world, of which 84 have their offices in Kyrgyzstan, and in 36 countries, Kyrgyzstan has diplomatic representation, and is a member of 77 international organizations[1].

The dilemma of Kyrgyzstan’s foreign policy is conditioned by the need to realize its national interests and the search for a strategic certainty in the context of globalization. To date, according to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Republic has established diplomatic relations with 135 countries of the world, of which 84 have their offices in Kyrgyzstan, and in 36 countries, Kyrgyzstan has diplomatic representation, and is a member of 77 international organizations[1].

Foreign policy as a dilemma

Very often, in public and academic discourse categories of single-vector and multi-vector policy are being used towards Central Asian states. If the single-vector policy can be effectively used within an empire, the multi-vector one can be regarded as a natural process of building friendly relations with all actors of global politics to maximize the benefits for sovereign states, as well as finding a balance between the influential powers.

It should be particularly noted that the foreign policy dilemma becomes a motive for an information war between the external actors who have geopolitical and geo-economic interests, not only in Kyrgyzstan and Central Asia, but also in the broader macro-region. Having said this, one should not exaggerate the importance of the republic for the external actors, nor should one reduce their efforts in the region to a fierce competition. Rather, Kyrgyzstan, due to its geographical location (proximity to China, its proximity to Afghanistan as a source of instability), historical past with Russia and its experience in liberalization of the political and economic system (which attracts US and the EU) has capabilities to build bilateral and multilateral relations. Up to date, the republic has experience of taking part in global international organizations and regional integration associations, with full participation in the decision-making process.

The multi-vector policy of Kyrgyzstan in the 1990s was conditioned by an urge to search for high-priority international investors and donors in order to solve pressing social and economic issues in view of Moscow’s passive interest in the Central Asian region as a whole. Since, at the time, both the Western academic community and international institutions were guided by the transition paradigm — the belief that the regimes carry out liberal reforms and strive for democracy, support for these reforms was the main on the agenda[2]. At that, international ratings of states had become not only an instrument of global governance[3], but also a key criteria for investment of money and was creating the image of the state in the international arena. Despite the fact that huge funds had been allocated to the country, the level of wellbeing and incomes changed insignificantly. Thus, Kyrgyzstan received $1.22 billion only for the period of 1992-2010, figuring as the third on the list of US donor-funding recipients among post-Soviet states[4].

Table 1. GDP per capita, according to UNDP reports (thousand USD)

Source: Compiled by the author based on data from UNDP’s Human Development Index

Source: Compiled by the author based on data from UNDP’s Human Development Index

International financial institutions were giving money for certain purposes, but as a result received a “gray zone” from sufficiently strong authoritarian regimes with a corrupt government system. The grants and investments received, in addition to the obvious benefits they brought, were also conducive not only to the strengthening of authoritarian trends, but also the creation of a corrupt state system that goes beyond the republic and is of a transnational character.

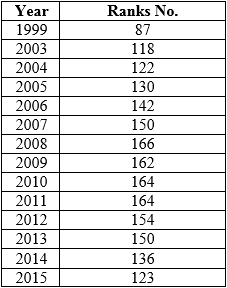

Table 2. Corruption Perception Index for Kyrgyzstan as of 1999 and, between 2003 and 2015.

Source: Compiled by the author based on an annual report on CPI – Corruption Perception Index, Transparency International. In Kyrgyzstan, the surveys were conducted in 1999 and since 2003 consistently every year.

However, two decades later, not only did the very paradigm of transition receive widespread criticism among scholars, but also the international donors reconsidered their performance.

Single-vector politics as a dominant trend

After the events of 2005 and 2010 multi-vector policy is being viewed in the country with ambiguity under active information pressure from the outside, where multi-vector politics began to be called “political prostitution”, while Moscow seen as a key foreign policy partner. Certainly, instrumental in this was also — an active interest of Russia in Central Asia and the intent to recover its dominant influence in the region through integration associations and information policy to discredit the “color revolutions” and Western institutions, as donors of those revolutions. In this context, note should be made of the initiated draft laws — on the activities of NGOs/NCOs as foreign agents, activation of movements against LGBTs and accusations of Western countries in support of these groups, which leads, in their opinion, to a subversion of traditional values, etc. Whereas previously, Kyrgyzstan agreed to open military bases for both the US (the antiterrorist coalition) and Russia (CSTO), then after 2010 the single-vector policy toward the Kremlin has become the dominant trend. However, diplomatic relations were established with 17 countries, mainly from the African continent, after 2010.

Table 3. States with which the KR established diplomatic relations after 2010

Source: Compiled by the author based on data from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the KR[5]

In the 1990s the multi-vector policy emerged as a reaction to the decline of Russia’s role in the region and the need to address socio-economic problems by means of international financial assistance. However, with the activation of the US in Central Asia, especially with the beginning of military operations in Afghanistan, we are seeing increasing interest of Moscow and Beijing in the region within the framework of supranational organizations as the SCO, CSTO, EurAsEC / EAEC. Whereas during the whole of the 1990s the integration associations were of declarative character, the US military and political presence in the region seriously concerned Russia and China, forcing them to look for a new framework of institutional cooperation with the Central Asian states.

The integration associations themselves, on the one hand, are increasingly becoming a strategic tool of domination by the major powers through attempts to format the foreign policy of the member countries, which further leads to competition for spheres of influence[6]. On the other hand, external actors tend to focus on the economic component of integration associations, rather than political values or security issues.

Is there a need for a multi-vector policy?

The dilemma for the multi-vector foreign policy of Kyrgyzstan — the question of choice of strategic partners for long-term cooperation, which, to date, has a number of characteristics. First, the partners must not be in the geopolitical conflict with Russia, because Moscow’s influence is retained and is the preferred actor in terms of the country’s population, given the substantial number of migrant workers and the importance of Russian as an official language. Second, readiness to invest real money in the economy of the republic. In this aspect there is no competition yet for China and its companies, but so far Beijing has not contested the role of Moscow in the region, which will likely lead to their cooperation with the division of responsibilities and intensification of integration capabilities.

After 2010, the question of a need to select a single strategic partner and the devaluation of the multi-vector policy acquired an acute tone in Kyrgyzstan. Observation over the presidential elections of 2011 and the parliamentary elections of 2010 and 2015 shows that the figure of Vladimir Putin had the greatest authority among the candidates during the election campaign, and the accession to the Customs Union and the EAEC virtually divided public opinion into two camps – supporters (pro-Russian part) and opponents (anti-Russian part). Migration to Russia continues to be important even in the face of declining economic indicators in the context of sanctions and the reduction of trade turnover between the states and the volume of transfers of labor migrants.

One of the serious challenges for bilateral relations was the denunciation of the agreement between the Russian Federation and the Kyrgyz Republic on the construction of the Upper Naryn cascade of the HPP and the HPP Kamabar Ata-1 as of 2012. A statement was made about the incapacity of the Russian side to finance the projects in the context of the sanctions[7] with the decision to denunciate the agreements in January 2016. Whilst for Kyrgyzstan the question of the construction of hydropower plants is a vital one, then, for Russian companies it became an economically inviable and geopolitically acute one, given the protests of Uzbekistan and its importance for the success of integration associations of Moscow[8]. After that, the country has been attempting to attract other investors to complete the projects.

In general, Kyrgyzstan’s foreign policy is changing due to, both internal challenges and in consideration of the regional balance of forces and the capabilities of the powers concerned. Defending one’s own interests and developing a multi-vector policy is the most preferred option in the era of globalization, when only multilateral diplomacy will serve the interests of states. Kyrgyzstan has all the capabilities to realize itself as a worthy and predictable partner in international relations.

References cited:

[1] http://www.mfa.gov.kg/index

[2] Carothers T. The End of the Transition Paradigm // Journal of Democracy. – 2002. – № 13(1).

[3] Ranking the World. Grading States as a Tool of Global Governance. Editors. Cooley A. and J. Snyder. – Cambridge University Press. 2015.

[4] Nichol, Jim. Kyrgyzstan: Recent Developments and US Interests. October 26, 2012. CRS Report for Congress // www.crs.gov. (10-11-2012)

[5] http://www.mfa.gov.kg/contents/view/id/98

[6] Akmatalieva A.M. Playing strategic games of integration as a way to format geopolitical preferences of states: the annual interuniversity conference materials – Bishkek, 2016. – С. 15-20.

[7] http://www.kyrgyzkorm.kg/news/press-konferenciya-almazbeka-atambaeva-video-polnaya-versiya.html

[8] Vasilivetsky A. Why Kyrgyzstan refused to build a hydroelectric power station with Russia http://inosmi.ru/country_kirgiz/20160124/235151232.html

Author: Ainura Akmatalieva, a political scientist, Director of the Institute of Advanced Politics (Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek).

The views of the author may not coincide with the position of cabar.asia