“The most alarming trend on a regional scale is the increasing extent of youth migration when young people, leaving to study abroad, stay there to obtain permanent residence.” – expert Olga Simakova, writing specially for cabar.asia, analyzes migration issues in Kazakhstan.

Follow us on LinkedIn!

In 25 years of independence for the countries of the former USSR, there were not only radical political and socio-economic changes but also significant demographic transformations. One of the demographic phenomena, which for various reasons has recently attracted the greatest attention on the part of both the general public and interested individuals, is migration or spatial mobility.

In 25 years of independence for the countries of the former USSR, there were not only radical political and socio-economic changes but also significant demographic transformations. One of the demographic phenomena, which for various reasons has recently attracted the greatest attention on the part of both the general public and interested individuals, is migration or spatial mobility.

Currently in Kazakhstan, as in other post-Soviet republics, there exist all the major types of migratory movements: foreign (international) and internal, permanent and temporary, legitimate (legal), unregulated and unlawful (illegal), voluntary and forced, etc.[1] Freedom of movement is a fundamental human right included in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1948 (Article 13) and enshrined in the basic laws of an overwhelming number of countries, including Kazakhstan (RK Constitution, Article 21). But, upon realizing their personal freedom of movement, the individual becomes a party to a much more complex process than simply a change of address, and their actions have become an object of research and analysis.

The Experience of Foreign Migration

Our field of interest in this article will be issues of foreign migration in Kazakhstan. It should be noted that since 1991, Kazakhstan has experienced several waves of foreign migration. According to estimates by Elena Sadovskaya, the country experienced a “stage of rapid and spontaneous development” during which “it significantly changed the direction of migration by forming new views, developed and reformed immigration policies, legislation, and institutions of governance”.[2] When compared with the 1990s, the annual number of immigrants to date has decreased tenfold from 300,000 to 30,000 while from 2004–12 there was a positive migration balance.

However, over the years of Kazakhstan’s independence, it has suffered significant losses according to experts. Thus in the period from 1991 to 1998, the country lost nearly 2.5 million people or 15% of the total population to foreign irregular migration.[3] In particular, the country has lost a large German community, which numbered at 956,00 according to the 1989 census, but at the beginning of 2014 the number of Germans in Kazakhstan numbered only 181,928 people (1.06% of the population).

The country has undergone significant demographic strain and, in fact, the socio-professional structure of society and its intellectual and educational potential continues to do so. Only in the last three years (2013-15), the total number of specialists with higher, partial higher, and secondary vocational education (for those over 15 years of age) who permanently emigrated from the Republic of Kazakhstan amounted to 47,400 people, and their share in 2015 alone amounted to 74.9% of the total number of those departing. In 2015, 17,418 professionals retired from the state, of which 26.1% had a technical background such as economics (13.2%), pedagogy (9,1%), health care (4.8%), etc.[4]

A Negative Balance

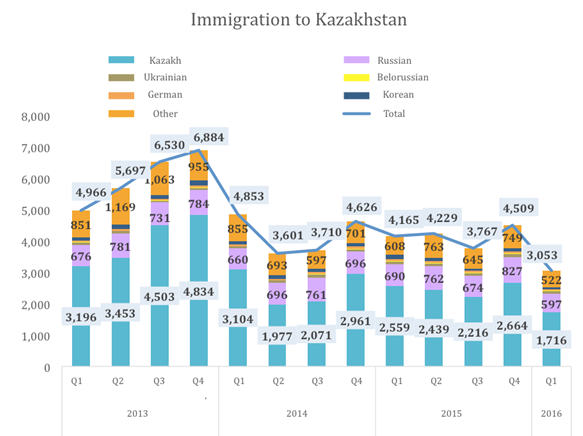

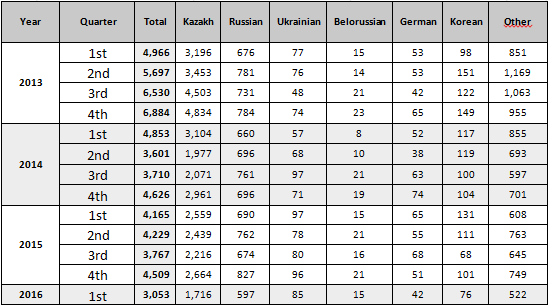

Particular attention is given to issues regarding the structural features of migration analysis such as the intensity of migration flows stemming from ethnic affiliation. Analysis of statistical data shows that during the period from 2013 to 2015, the flow of immigrants into the country tended to decrease. If in the 4th quarter of 2013 the number of arrivals to the country amounted to 24,100, in 2015 this figure totaled 16,700.

60% of all new arrivals were ethnic Kazakhs while Russians came in second. Despite the fact that the total number of Russians moving to Kazakhstan annually for permanent residence for the past three years has remained virtually unchanged, their ethnic proportion among immigrants has increased significantly from 13.6% in 2013 to 17.4% in 2015.

Figure 1. Immigration to Kazakhstan from Q1 2013 to Q1 2016[5]

Unfortunately, the increase in immigration flow does not compensate for the losses to emigration. According to the Statistics Committee of the Ministry of National Economy, if 24,400 people emigrated from the country in 2013, then it reached 30,100 in 2015. At the same time during the period under consideration, there remained an increasing trend of Russian, German, Kazakh, and Korean immigrants. For example, 70-71% of immigrants are ethnic Russian, 6.8% are German, 6.7% are Ukrainian, and 4-5% are Kazakh.

Those most likely to emigrate reside in the northern and northeastern regions of the country bordering the Russian Federation. By the end of 2015, it was mainly residents of Karaganda (4,600), Eastern-Kazakhstan (4,200), Pavlodar (3,400) and Kostanai (3,300) districts who left to seek permanent residence abroad. The western and southwestern regions of Kazakhstan, which are dominated by ethnic Kazakhs, witnessed the lowest net emigration. For example, there were only 523 from Mangistau oblast, 170 from Atyrau oblast, and 59 from Kyzylorda oblast.[6]

Figure 2. Emigration from Kazakhstan from Q1 2013 to Q1 2016

Analysis of the statistical data shows that Q3 is the most favorable period for foreign migration. During this stretch, emigration processes peak in Kazakhstan. This can be attributed to both the temperate weather, which is the most convenient for traveling, and the beginning of the school year. But, if one looks at immigration, Q4 is the most favorable time.

The balance of migration in Kazakhstan for the last three years has been negative. Unfortunately, in the information space the main focus was on the high level of Russian and European ethnic groups’ migration. But this interpretation is ambiguous. We must understand that in calculating net migration two indicators must be accounted for – the number of immigrants and the number of emigrants. Analyzing the dynamics of both indicators over the past three years leads to the conclusion that migration was largely negative with net emigration being 1.5 times higher than immigration, i.e. from 24,077 entering the country in 2013 to 16,670 in 2015 versus the increase in cases of emigration.

Figure 3. Net migration from Kazakhstan from Q1 2013 to Q1 2016

If we speak about popular destinations, the most (25,600) left for Russia. Germany was second with 2,000, Belarus with 605, followed by Uzbekistan with 364, and the US with 265. Canada and Israel are also popular countries for Kazakhstanis who wish to leave the country.

Forced Migration

It is noteworthy that survey results show a low migration potential for Kazakhstanis. On the question of whether they would like to move to another location (urban/rural, region, country), most answered negatively. The percentage of those who expressed a desire to move was no more than 25%.

Oftentimes, migration is forced and usually in conjunction with an individual’s or their family’s specific circumstances. More often than not those 25-40 years of age are involved in migration thus representing the economically active part of the population. According to sociological data results (population surveys), the main reason for emigration at the moment is socio-economic problems, which are based on dissatisfaction with the current standard of living and employment prospects. Family circumstances and those of a personal nature are also relevant. In this case, the main motives are the concern for the health and future of their family. As experience shows, the unfavorable ecological situation in the region or the inability to provide professional education for their children may tip the scales in favor of emigration.[7]

Of the main migration patterns that have developed in Kazakhstan, E. Sadovskaya identifies the following:

- Firstly, diversification of types migrations with predominance of labor and educational migration;

- Secondly, the prevalence of temporary migration abroad with a tendency to transform into permanence (relocation to a permanent place of residence and acquisition of citizenship);

- Thirdly, there is a growing trend of women and youth migration over the past 10-15 years;

- Fourth, the role of diasporas, ethnic minorities involved in organizing and maintaining migration, and their involvement in solving migrants’ problems.[8]

Old vs. New Risks

Unfortunately, data from the Statistics Committee clearly indicate that there is a growing trend of emigration flow for the last three years. In 2014, it grew by 25% compared to 2013 and, according to 2015 results, has held at the same level. It should be noted that the greatest impact in terms of information on migration in Kazakhstan is received in connection with the high degree of Russian and Russian-speaking populations. But if we look at the ethnic structure of immigrants from 2013-15, it has remained the same despite the increase in the total number of those leaving. Those who speak about a new wave of Russian migration from Kazakhstan without further study are not correct. The most alarming trend on a regional scale is the increasing extent of youth migration when young people, leaving to study abroad, stay there to obtain permanent residence.

Nevertheless, from the point of view of demographic analysis, the migration situation at the moment in Kazakhstan cannot be called dramatic. One can agree with E. Sadovskaya’s opinion that in recent years Kazakhstan “has entered a period of relatively controlled movement.”[9] The processes of population movement have not occurred at the expense of the most important demographic indicator, total population. The country has seen an annual population increase, which is primarily dependent on natural growth rather than mechanical factors, i.e. migration.

References

[1] Sadovskaya, Elena. “International Migration to Kazakhstan in the Period of Sovereign Development.” Kazakhstan Specter 75, no. 1 (2016): 7–42. http://www.kisi.kz/uploads/33/files/348Has08.pdf.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Committee on Statistics of the Ministry of National Economy of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Демографический ежегодник Казахстана [Demographic Yearbook of Kazakhstan]. Edited by A. A. Smailov. Astana, 2015. http://www.stat.gov.kz/faces/wcnav_externalId/publicationsCompilations2015?_afrLoop=6768752651795750#%40%3F_afrLoop%3D6768752651795750%26_adf.ctrl-state%3Df3gqyhy5u_21.

[4] Elena Sadovskaya, “International Migration to Kazakhstan in the Period of Soviet Development”.

[5] Ministry of National Economy of the Republic of Kazakhstan Committee on Statistics. Statistical Indicators. Edited by A. A. Smailov. Vol. 1. Astana, 2015. http://stat.gov.kz/faces/wcnav_externalId/publicationsJournals?lang=ru&_afrLoop=6932138545609899#%40%3F_afrLoop%3D6932138545609899%26lang%3Dru%26_adf.ctrl-state%3Dmhej1pvdb_77.; ———. Statistical Indicators. Edited by N. S. Aidapkelov. Vol. 3. Astana, 2016. Ministry of National Economy of the Republic of Kazakhstan Committee on Statistics. Statistical Indicators. Edited by A. A. Smailov. Vol. 1. Astana, 2015. http://stat.gov.kz/faces/wcnav_externalId/publicationsJournals?lang=ru&_afrLoop=6932138545609899#%40%3F_afrLoop%3D6932138545609899%26lang%3Dru%26_adf.ctrl-state%3Dmhej1pvdb_77.

[6] Kidaibergenov, Arman. “Русские, немцы и украинцы уезжают из Казахстана — статистика” [Russian, Germans, and Ukrainians are leaving Kazakhstan – Statistics]. 365info.kz, April 22, 2016. http://365info.kz/2016/04/vse-bolshe-kazahstantsev-emigriruet-za-rubezh-komstat/.

[7] Simakova, Olga. “Emigration of the Russians: An Invitation to Reflect.” Kazakhstan Specter 75, no. 1 (2016): 99–109. http://www.kisi.kz/uploads/33/files/348Has08.pdf.

[8] Elena Sadovskaya, “International Migration to Kazakhstan in the Period of Soviet Development”.

[9] Ibid.

Author: Olga Simakova, Public Fund “Center for Social and Political Studies ‘Strategy’” (Almaty, Kazakhstan)

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the view of cabar.asia