“From time to time there is discussion of the necessity of resorting to methods of stimulating the return of migrants. Migration, as a rule, weakens the economy of the sending country due to the drain on its human resources and becomes a source of conflict in the receiving country between local residents and the recent arrivals,” – Economist Nazik Beishenali examines the possible solutions for Kyrgyzstan’s migration problem in this cabar.asia exclusive.

The positive and negative aspects of migration

The positive and negative aspects of migration

Labor migration has, without a doubt, positive economic benefits for the sending state. However, it is important to examine migration not only from the point-of-view of its short-term benefits but also with a consideration of the long-term perspectives for economic growth and social development in the sending country.

The lion’s share of government activity with regards to migration is aimed at solving short-term issues for improving the migrants’ living conditions and protecting their rights in the receiving states.

This is an important field to work in, but less effort is spent on forming a vision for issues in the mid-term: what are the pros and cons in the context of dynamically developing economic conditions, what is being done to create employment opportunities at home, and what stimuli are being created to attract migrants to come back and decrease the number of new migrants?

As a whole, the relationship of the Kyrgyzstani state and society to labor migration can be considered to be mostly positive, although there is periodic discussion of the risks and threats of “brain drain” and a loss of the manufacturing potential of the working-age population.[1] Additionally, when the issues of migration are discussed, attention is predominantly drawn to economic aspects even though the consequences of mass migration on the demographic, cultural, and social development of a country are also important. One of the primary expectations upon Kyrgyzstan’s ascension to the Customs Union, and later the Eurasian Economic Union (EaEU), was the attraction of new investment into labor-intensive sectors of the economy, domestic job creation, and the regulation of migration flows and legislation. However, currently the investment difficulties of EaEU member-states, political circumstances including the absence of a unified vision on employment, as well as economic and social policies writ large retard the process of meeting goals and, as such, demands new approaches to solving problems that arise.

The dynamics of migration processes

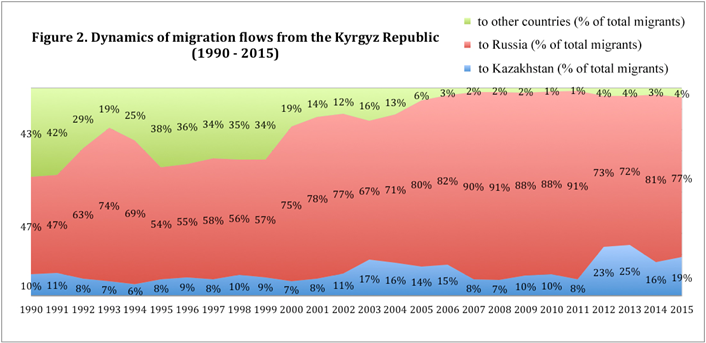

Russia and Kazakhstan remain the primary destinations for Kyrgyzstani labor migrants. According to the Russian Federal Migration Service’s official data, there are about 500,000 Kyrgyzstani migrants in Russia. In 2015, Russia accepted 77% of all migrants from the Kyrgyz Republic while, according to official statistics, 18% of labor migrants went to Kazakhstan (NSC, 2016). It is an accepted fact that the primary causes behind this migration are the so-called “push factors” such as the lack of employment prospects and low-income levels in the Kyrgyz Republic, however pull factors also influence people’s decision to migrate. These pull factors are not only arise from the economic benefits and geographic and cultural proximity of the two countries but are also due to the ever-strengthening networks of co-nationals.

Moreover, the main factor driving the introduction of liberal migration legislation is the growing demand in the Russian labor market due to demographic conditions stemming from Russia’s aging population. According to an analysis by the CIS Statistical Committee, the Russian population could possibly drop to less than 90 million people (a 40% decrease from 2010 levels), and nearly all scenarios for Russia’s demographic development involve a decline according to Anatolii Vishnevski, director of the Institute of Demography at the National Research University’s Higher School of Economics. Dr. Vishnevski says, “If it is not possible to successfully move to a process of natural demographic increase or change the natural level of attrition, then the only remaining resource is immigration. It would be possible to increase the population through positive immigration flows.”[2] The looming prospects of a demographic crisis lead to a situation in which “migration flows become important for the improvement of the demographic situation and could compensate… to a degree, for population decline.[3]

The dynamics of migration flows from the Kyrgyz Republic to the Russian Federation indicate a decrease in the number of people emigrating with the goal of earning money before 2015 (fig. 1).

This trend can best be explained by the recent crises in the Russian and Kazakhstani economies, which have impacted, labor market opportunities and led to a decrease in the job opportunities available to labor migrants. It is possible that this could also be explained by an increase in the number of labor migrants gaining citizenship in the receiving countries and thus ceasing to be considered migrants for all intents and purposes. However, according to data from the Russian Federal Statistics Service (2016), there has been a noted increase in the migration flows from Kyrgyzstan in the population exchanges among CIS member-states in the first half of 2016. If there was a gain of 2,792 people in the first half of 2015, then there was a gain of 7,686 in 2016, which is 2.75 times greater. Taken as a whole, the number of Kyrgyzstani migrants in receiving states remains relatively stable. According to statistics from the Federal Migration Service, in 2014 there were roughly half a million migrants from the Kyrgyz Republic in the Russian Federation.

Source: the above graph was created by the author based on data from the National Statistical Committee (2016)

Source: the above graph was created by the author based on data from the National Statistical Committee (2016)

Source: the above graph was created by the author based on data from the National Statistical Committee (2016)

Source: the above graph was created by the author based on data from the National Statistical Committee (2016)

There still aren’t any prospects for finding employment at home

According to media reports, the position of migrants is such that, if there were opportunities to find employment, the migrants would come back home. That being said, there is no data showing that the Kyrgyzstani labor market would be able to absorb its domestic labor force in the near-term. The Kyrgyzstani labor market relies primarily on the agricultural, service, and trade sectors, which have high levels of self-employed people in low-paying, seasonal, and unstable forms of employment.

Moreover, the Kyrgyzstani labor market is characterized by many structural problems such as a mismatch between the needs of the market and the education of the population, a lack of regional development programs that would foster the job creation, the absence of programmatic support for small and medium enterprises and cooperatives which act as the primary source of employment around the world, and, finally, a lack of updated employment policies.

As a result, Kyrgyzstan is faced with unemployment, informal employment, and migration. In Russia and Kazakhstan, with their developed manufacturing, education, and health sectors providing more than 60% of all jobs, labor migrants are attracted by comparatively high wages (which are nearly 10 times higher than the average wage in Kyrgyzstan) and relatively stable and secure employment.[4]

First and foremost, unemployment in Kyrgyzstan impacts young people. According to the National Statistics Committee (2015), the unemployment rate was officially at 8.1% in 2014, but it reached 14.7% for young people. Nearly 40% of young people officially registered as unemployed have been out of work for a long period of time, and more than a few of these individuals have a college education (14%). The majority of the unemployed have a secondary or higher education, which seems unhelpful for them in finding employment. There is also the problem of degrees, on one hand, not corresponding to the actual education received while not corresponding to the employment opportunities in the country on the other hand. The result of this dual inconsistency is emigration to other countries where people are able to find employment and low-skilled labor is better paid.

Remittances from Labor Migrants: an Eternal Phenomenon?

Kyrgyzstan is ranked third among countries with high levels of remittances in relation to GDP. In 2014, remittances accounted for 30.3% of the Kyrgyz Republic’s GDP (Centre for Migration Policy, 2015).[5]

Remittances have allowed the Kyrgyzstani population, particularly in rural regions, to improve their standard of living and increase their access to social infrastructure. Remittances have also allowed for a certain amount of entrepreneurial activity and helped the country cover, to a large degree, its labor balance deficit. It is a fact that the earnings of labor migrants primarily finance the daily needs of migrants’ families and are invested in real estate and other property.

Remittances, as a rule, are cashed and spent by the migrants’ families. If these remittances are saved, then it is only in cash form. It cannot be said that remittances have led to any depreciation of the resource base of banks or contributed to lower interest rates.

Although there is no concrete data on how the experiences and remittances of labor migrants have led to any increased know-how or innovative projects, it must nevertheless be noted that these remittances have impacted consumer spending and trade. Small investments are made in purchasing livestock and in agricultural projects. Various business projects are realized on the basis of migrant savings, but these projects remain small-scale ventures with a short lifespan. There are some cases of Kyrgyzstani migrants successfully starting businesses in Russia and Kazakhstan, and one could presuppose that this trend may positively impact the development of certain economic sectors and the strengthening of trade ties. The activity of the diaspora in intensifying trade relations between Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Kazakhstan, the creation of sales channels for products from Kyrgyzstan, as well as the development of transportation and logistical services are some of the main beneficial effects of migration.

Migration in Kyrgyzstan is a relatively new phenomenon and it is likely that the flow of remittances will remain over the coming years. Moreover, considering the relative geographic proximity between the countries, labor migrants do not disassociate their futures from that of the Kyrgyz Republic even after receiving citizenship or permanent residency abroad. As such, they will continue to invest in real estate and business ventures, which provides linkages to their homeland. Considering the direct correlation between the intensity of familial relations and the level of remittances sent, migrants, in Kyrgyz society, will continue to maintain a financial connection to their homeland as long as their parents are alive. It would be useful to reveal the motivations of labor migrants to send remittances. To what degree are these remittances altruistically aimed at caring for a family, and to what degree are they pragmatically spent on construction or the renovation of a migrant’s personal property? The most important question regarding these remittances is how long they will continue. If the most important benefit from migration were to disappear over time, then what reasons would there be to not hinder the massive labor flows leaving Kyrgyzstan?

The economic crisis and currency devaluations in Russia and Kazakhstan have led to a decrease in remittances in recent years, and, despite the fact that they have recovered to an extent in 2016, it is likely that the bulk of the personal expenses of migrants will gradually move to their country of residence. It should be noted that the average age of a labor migrant is 29,[6] and, when a migrant moves with their family and gains citizenship in the host country, it can be assumed that the bulk of their household spending will shift over time to the receiving country. Moreover, global trends in remittances show that there is a direct correlation between how long an individual lives in a receiving country with the amount of remittances sent back to the sending country.

What’s next?

If in the medium term the Kyrgyz Republic must continue its course of developing its economy and creating employment opportunities, then what are the possible variations in approaching the regulation of migrant flows from a short-term state policy perspective?

- Things could remain unchanged, i.e. rely on the natural course of events, which more or less characterizes the current situation. In this scenario’s worst case, the innovative and manufacturing potential of the Kyrgyzstani economy would continue to deteriorate, which would only worsen the economic and social crisis in the country and exacerbate domestic security issues. Best case, the diaspora and co-national associations would become centers for entrepreneurial activity, and if these linkages are not broken due to some geographic or political factors, they could gradually promote the specialization of the Kyrgyzstani economy as a provider of certain products for EaEU markets.

- From time to time there is discussion of the necessity of resorting to methods of stimulating the return of migrants. Migration, as a rule, weakens the economy of the sending country due to the drain on its human resources and becomes a source of conflict in the receiving country between local residents and the recent arrivals. Due to this, in some countries, both sides may be interested in beginning programs to aid in the return of migrants. In Kyrgyzstan however, a program such as this could be presented only as a component of a national economic program, because currently there is objectively nowhere for the migrants to return to. In the event of a massive return of labor migrants, there could be a deepening of tension in the labor market. Correspondingly, this result is fraught with economic imbalances and social cataclysms. A report from the Eurasian Economic Bank’s Centre for Integration Research (2015) provides examples of programs for returning migrants that are implemented by a variety of European countries and aimed at gradually integrating returnees into the economy of the sending country. However, in the short-term it is unlikely that Russia or Kazakhstan will support these types of initiatives considering their internal demographic situational and the political priorities of regional integration.

- A search for new solutions drawn from the experiences of countries like India, which witnessed a large labor migration outflow. India has one of the largest populations of emigrated citizens (Centre for Migration Policy, 2015) and maintains the “Person of Indian Origin” status. This is a lifelong stamp in a passport that allows former Indian citizens as well as other categories of individuals (e.g. foreign nationals with an Indian ancestor going back for up to four generations, foreign children and spouses of Indian citizens, etc.) visa free entry into and exit from India and permanent residency in India. This stamp also frees an individual from many administrative delays in gaining employment, purchasing a home, adoption, etc. Because the Indian Constitution does not allow for dual citizenship, in 2005 the Indian Prime Minister introduced the “Overseas Citizenship of India” program[7], which may be of interest to the Kyrgyz Republic to study this practice.

References:

[1] Karabchuk, T. et al. 2015. “Трудовая миграция и трудоемкие отрасли в Кыргызстане и Таджикистане: возможности для человеческого развития в Центральной Азии (Labor migration and labor-intensive industries in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan: opportunities for human development in Central Asia).” Eurasian Economic Bank, Centre for Integration Research: St. Petersburg. http://eabr.org/general/upload/CII%20-%20izdania/2015/Report_CA_Labour_Migration_and_Labour_Intensive_Sectors_Full_RUS.pdf

[2] Vishnevskii, A. 2007. “Россия в мировом демографическом контексте (Russia in the global demographic context).” 22 November. Polit.ru. http://polit.ru/article/2008/02/07/vyshnevsky/

[3] Iontsev, V., I. Ivakhnyuk, and I. Aleshkovskii. 2009. “Международная миграция и ВИЧ в России (International migration and HIV in Russia).” In International population migration: Russia and the Modern World, ed. V. A. Iontsev. No. 21.

[4] Karabchuk, T. et al. 2015.

[5] ibid

[6] Beishenali, N. et al. 2013. “Последствия вступления Кыргызстана в Таможенный союз и ЕЭП для рынка труда и человеческого капитала страны (The consequences of Kyrgyzstan joining the Customs Union and Common Economic Space for the labor market and human capital of the country).” Eurasian Economic Bank, Centre for Integration Research: St. Petersburg. http://www.eabr.org/general//upload/CII%20-%20izdania/Proekti%20i%20dokladi/Kyrgyzstan%20-%20CU/EDB_Centre_Report_13_Full_Rus_1.pdf

[7] Indian Embassy, Moscow. “Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI) Scheme.” http://www.indianembassy.ru/index.php/en/consular-services/oci

Statistics drawn from the National Statistics Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic, the National Bank of the Kyrgyz Republic, and the Federal Service of National Statistics of the Russian Federation.

Author: Nazik Beishenaly, President, Union of Cooperatives of Kyrgyzstan (Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek)

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the view of cabar.asia