“In the upcoming May 22nd referendum there are plans to lower the age limit for presidential candidates from 35 to 30, which will open the door for Emomali Rahmon’s son, Rustami Emomali, to run for president in the 2020 elections”, – political scientist Khursand Khurramov analyzes the Azerbaijan-style succession scenario in Tajikistan in a cabar.asia exclusive.

Follow us on LinkedIn!

Recently the domestic political and social processes in Tajikistan have been under increasing scrutiny by international media. These events have included the closure of the opposition Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT), the defection of Gulmurod Khalimov, a high-ranking Tajik special forces commander, to the Islamic State, as well as the mysterious mutiny of Deputy Defense Minister Abduhalim Nazarzoda. Experts and observers see the reasons behind these outbursts of instability in the political regime’s transformation into a hard authoritarian system.

Recently the domestic political and social processes in Tajikistan have been under increasing scrutiny by international media. These events have included the closure of the opposition Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT), the defection of Gulmurod Khalimov, a high-ranking Tajik special forces commander, to the Islamic State, as well as the mysterious mutiny of Deputy Defense Minister Abduhalim Nazarzoda. Experts and observers see the reasons behind these outbursts of instability in the political regime’s transformation into a hard authoritarian system.

Even though authoritarian tendencies in the region began taking shape almost immediately after the republics gained independence, Tajikistan was affected by this trend much later for objective reasons. This was, first of all, due to the weak institutionalization of the government after the civil war, the relatively strong opposition, and the lack of adequate financial and economic resources on the part of the ruling regime. It seems that the sum total of these factors influenced the later political transformation of the regime.

Reform for the Sake of Power

The institutionalization of power in Tajikistan took place in parallel with the weakening, co-optation, and in some cases the complete removal of opposition forces from the field of politics.

The appearance of political Islam in the form of the IRPT as an influential actor capable of changing the outcome of the game to a certain degree was a distinctive feature of the political process in Tajikistan. The spread of Islamic ideas was an objective process filling the ideological vacuum facing the Republic after the collapse of the USSR. In some ways, the end of the civil war was made possible by the acceptance of this fact. A consensus was found on the role of Islamic ideas in politics, which was embodied by the 1999 referendum on certain amendments to the Tajik Constitution.

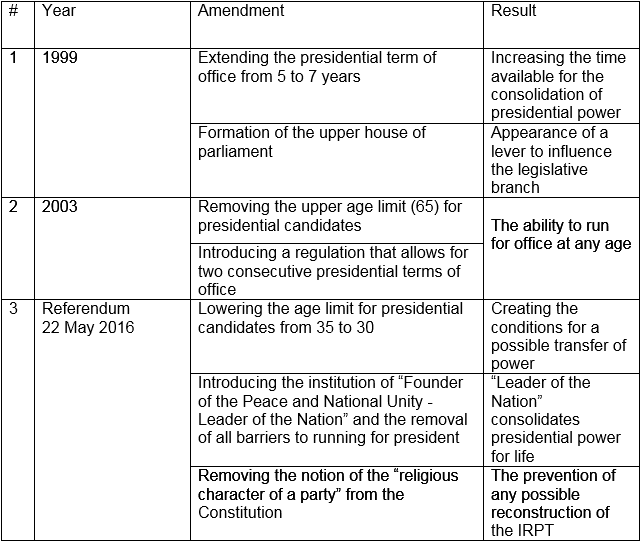

Amending the Constitution was necessary for the development of democratic processes and of ensuring stability in Tajikistan.[i] This reform was primarily instrumental as a mechanism for resolving the civil war – the disputes over the nature of the state, the formation of a new bicameral parliament, the holding of elections for the presidency, the Majilisi Oli (Parliament), and the local representative bodies.[ii]

However, alongside this strengthening of the political consensus, measures strengthening the power of the presidency were also added to the Constitution. These measures were expressed in how the upper house of parliament was formed, in the expanding of the President’s term of office from 5 to 7 years, in stipulating that the single-term limit applies only for later presidents, etc.[iii]

The formation of the upper house of parliament was to be undertaken through the elections of its members in joint meetings of local representatives, who, as regional governors, district chiefs, and city mayors, could simultaneously represent their local constituencies as well as the executive branch. As a result, elections to fill 75% of the seats of the upper house were organized by local government heads. The remaining 25% were appointed by presidential decree. Because all of the regional and district chiefs as well as city mayors were appointed by the President, he was given an effective tool to influence the outcome of elections.

The period of time after the first referendum (1999-2003) was characterized by the secular regime not preventing the increasing role of religion in society while simultaneously not allowing religious institutions and certain individuals to influence policymaking. Opposition parties functioned relatively openly and legally.

Driven by political expediency as well as the need to attract investment and for access to credit from Western institutions, a form of faux democracy was adopted. In practically any European Union (EU) document related to bilateral or multilateral relations with the Central Asian states, a heavy emphasis was placed on democratization, which often annoyed local elites. However, their historically reinforced tendency towards adaptation combined with an eastern cunning, as well as the willingness of the Europeans themselves to turn a blind eye on the costs of authoritarianism, made the politics of the EU fully compatible in Tajikistan.[iv]

The second constitutional reform took place in 2003 and was officially explained as being necessary to perfect the national legislation. The referendum imposed 122 amendments, however, alongside these technical changes and clarifications, there was a clearly visible effort to create conditions for the re-election of the incumbent president. Before the referendum, the candidates were eligible to run for office from the age of 35 to 65, but now only the lower age limit for candidates was to be preserved. Moreover, if the President could only be elected for one term before the constitutional referendum, then, according to the amendments, the same individual could hold this position for another two consecutive terms.[v]

Monopoly on Power as Instinct of Self-Preservation

By utilizing the public’s negative views of a resumption of the civil war and creating the conditions for extending the presidential term of office, the ruling regime was able to strengthen its domestic political position due to the presence of a legitimate, secular opposition as well as a number of former supporters of the President who, it would appear, had begun to abuse their positions. The individuals arrested and sentenced to lengthy prisons included the leader of the opposition Democratic Party, M. Iskandarov; the deputy head of the IRPT, Sh. Shamsuddinov; the former head of the Ministry of Interior Affairs and Customs Commission, Y. Salimov; and the former commander of the Presidential Guard, G. Mirzoev. These measures contributed to an obvious strengthening of an increasingly harsh ruling regime.

The Clan Factor and Succession Scenarios

Due to the fact that the ruling regime’s sustainability was based not on ideology or party discipline but on the distribution of economic rents, material benefit has been recognized as the foundation of loyalty to the authoritarian leader. This circumstance has dictated the necessity of monopolizing the economic sphere for maintaining the loyalty of powerful groups.

However, unlike other young post-soviet states (Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan), Tajikistan lacked a single economic sector over which a monopoly would allow the controlling of other domestic political and economic actors. Cotton cultivation, aluminum production, and energy have been the main economic sectors from the very beginning. Later, after the construction of road infrastructure with China and an increase in labor migration to Russia, the banking sector and customs duties became additional revenue-generating segments of the economy. As is to be expected based on the given logic, the President’s closest relatives were appointed to leadership positions in these economic sectors.

According to comments made by then-US Ambassador to Tajikistan Tracey Jacobson published by WikiLeaks in 2011, the large aluminum factory TALCO, while officially being state-owned (70%), “officially came under direct control of President Rahmon’s family in 2004,” and, although “the President’s brother-in-law, Hasan Sadullozoda, does not hold a title at TALCO, (he) has close ties with the company’s management and makes or endorses all major decisions.”[vi] In May 2015, the President’s son-in-law and former Deputy Finance Minister, Jamoliddin Nuraliev, was appointed to the position of Deputy Director of the National Bank. Meanwhile, the post of Minister of Energy and Industry was held until 2013 by the President’s father-in-law, Sherali Gulov, whose son is currently a Tajik consul to the Russian Federation. From 2013 to 2015 the Custom’s Service was led by the President’s son, Rustami Emomali, who was later named head of the Anticorruption Agency.

The list proving nepotism within the political system goes on and on. The information is no secret to observers of the political system within the country. The goal here was simply to demonstrate a handful of economic sectors that bring significant revenue to the state budget.

The Fragmented Opposition as a Factor in the Monopolization of Power

Elite fragmentation among opposition groups in the lead up to the 2013 presidential elections was yet an additional factor facilitating the monopolization of power in the country. The complete absence of consensus among the opposition on supporting a single, joint candidate demonstrated that the opposition is simply unable to compete with the regime.[vii] This moment was the point of no return for the legality of the IRPT’s political activities. The party did not mobilize the masses, and the secular forces within the opposition did not show any sign of support for the IRPT. As a result, the IRPT was completely forced out of the country’s political system.

Risks on the Path Towards the Formation of a Neo-Monarchy

Today the only realistic risk on the path towards the monopolization of power in the long-term is the economic stagnation and resulting popularization of radical sentiments in society.

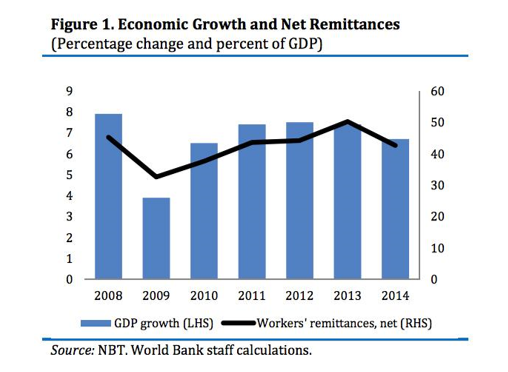

Tajikistan’s population, with an average age of about 25 and an annual growth rate of more than 2%, is one of the youngest and fastest growing in the region. The national economy is overly dependent on external sources of revenue.[viii] According to the World Bank, remittances from the Russian Federation alone comprise 42.7% of the Tajik GDP in 2014, making Tajikistan the most remittance dependent country in the world. The current economic downturn in Russia and recent changes to Russian immigration policy have led to a decrease in labor migration as well as an increase in the number of individuals looking for work in Tajikistan. This could, in turn, become a source of social tension.[ix]

According to the Tajik National Bank, after 19% growth in 2013, the cost of remittances in dollar values in 2014 decreased by 8.3% year-on-year.[x]

The poverty rate is increasing against a background of socio-economic ‘demodernization’. Before 2010, due to the civil war and economic difficulties, the urban population dropped to 26% of the total population,[xi] which is comparable with the least developed countries of the world. The emigration of highly qualified specialists and the intelligentsia can also be considered a manifestation of “demodernization”. The marginalization of an urban population prone to destructive acts increases the risks associated with civil unrest, particularly when questions of a referendum and the transfer of power in the not-too-distant future are on the agenda.

In the upcoming May 22nd referendum there are plans to lower the age limit for presidential candidates from 35 to 30,[xii] which will open the door for Emomali Rahmon’s son, Rustami Emomali, to run for president in the 2020 elections. Additionally, the new constitutional project strengthens the institute of the “Leader of the Nation” and gives the current president, Emomali Rahmon, the right to put forward his own candidacy without regard for term limits. The new constitutional project also calls for abolishing any allowances for the “religious character of a party”, which would completely eliminate any further dialogue regarding a return of the IRPT to the political stage. The main amendments to the Constitution of Tajikistan are considered below in table 1.

Table 1. Amendments to the Constitution of the Republic of Tajikistan

The historic examples of regional and global powers, primarily the United States, supporting Ilham Aliev and Bashar al-Assad shows that the international community is receptive to the transfer of power from father to son. This was due, first and foremost, to the economic interests of the great powers as well as the desire to maintain political stability in the given regions. However, the question of succession in Tajikistan is made more dangerous for the regime and for the preservation state itself due to the lack of economic perspectives for the population.It thus appears that the Parliament is creating the legal conditions for an Azerbaijani scenario – the transfer of power from father to son. In Azerbaijan, President Heydar Aliev put forward his candidacy even though his son, Ilham Aliev, was also running. The younger Aliev officially explained the logic behind his candidacy as an effort to help his father. However, due to his poor health, Heydar Aliev withdrew his candidacy two weeks before the elections to the benefit of his son.[xiii] This decision was met with mass protests in Baku that were summarily crushed, and the elections were declared valid even though international observers reported that the elections had been “far from international standards”.[xiv]It was Syria that set the precedent for lowering an age limit for a successor. After the death of President Hafez al-Assad, who had ruled Syria for 30 years, the Syrian Parliament amended the Constitution. They lowered the minimum age limit for a presidential candidate from 40 to 34 specifically to allow for the election of the President’s son, Bashar al-Assad. The relative stability of the regime was secured at the expense of growing unrest and discontent in society, which exploded into a tragic civil war in 2011.

The process of consolidating and monopolizing presidential power in Tajikistan began the minute the civil war ended. Initially the opposition, co-opted by the government, did its best to conform and, for all intents and purposes, lost its original status in political contests. Having been divided into small groups, the opposition was unable to present itself as an independent political actor, which led to its complete defeat. Labor migration out of the country and the resulting depoliticization of the population, which significantly lowered the risk of large-scale protests within the country, were significant factors in the unwitting strengthening of authoritarianism. It would be naive to think that the political regime will begin to develop democratically due to external factors. The consolidation of power will continue in conjunction with the formation of new domestic political models that draw increasingly less from liberalism and meet the needs of the ruling elite.

References:

[i] Khakimov, Sh. 2013. “Constitutionalism in Tajikistan: The Path to Democracy or the Strengthening of Authoritarianism? (Конституционализм в Таджикистане: Путь к демократизации или укрепления авторитаризма?)” Central Asia and the Caucauses. №1. p 40

[ii] “Project for the Amending of the Constitution of the Republic of Tajikistan (Проект по изменению и дополнению Конституции Республики Таджикистан).” 1999. Dushanbe: Sharki ozod. p 29.

[iii] “Project on the Amending of the Constitution of the Republic of Tajikistan (Проект по изменению и дополнению Конституции Республики Таджикистан).” 2003. Dushanbe: TASFETO (ТАСФЭТО). p 30.

[iv] Zvyagelskaya, I. D. 2011. “Authoritarianism in Central Asia (Авторитаризм в Центральной Азии).” from Chto dogonyaet dogonyayushee razvitie, ed. A. Petrov. Moscow: Russian Academy of Sciences Institute of Eastern Studies.

[v] Krastev I. 2011. “Paradoxes of the New Authoritarianism.” Journal of Democracy, 22 (2). pp. 5-16.

[vi] Avesta.tj. “WikiLeaks. Who Owns a 30% share in TALCO Management? (Кому принадлежит 30% доли Talco Management?).” 3 June 2011. http://www.avesta.tj/main/8605-wikileakes-komu-prinadlezhit-30-doli-talco.html

[vii] Khurramov, Kh. “The properties of the relationship between opposition and the government at this stage in Tajikistan (Хуррамов Х. Особенности взаимоотношения оппозиции и власти в Таджикистане на современном этапе).” material from the Current Problems in the Post-Soviet Space (Актуальные проблемы постсоветского пространство) conference. 2 April 2015. Moscow: Diplomatic Academy.

[viii] World Bank Group. 2015. “Tajikistan: Slowing Growth, Rising Uncertainties: Tajikistan Economic Update No. 1, Spring 2015.” https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/Publications/ECA/centralasia/Tajikistan-Economic-Update-Spring-2015-en.pdf

[ix] ibid, 2015.

[x] ibid, 2015.

[xi] Kazantsev A. 2016. “Valdai Paper #2 (42): Сentral Аsia: Secular Statehood Challenged by Radical Islam.” Valdai Club. http://valdaiclub.com/files/9605/

[xii] Panfilova, V. “The constitution is being rewritten in Tajikistan (В Таджикистане переписывают Конституцию).” Nezavisimaya Gazeta. 13 January 2016. http://www.ng.ru/cis/2016-01-13/7_tajikistan.html

[xiii] Zhabrov, A. and P. Korolev. 2014. “Democratic Transition in the Post-Soviet Space: The Peculiarities of the Institute of Presidential Successors (Демократический транзит на постсоциалистическом пространстве: особенности института преемничества президентской власти).” Izvestia Tulskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta, Gumanitarnye nauki. No. 3 http://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/demokraticheskiy-tranzit-na-postsotsialisticheskom-prostranstve-osobennosti-instituta-preemnichestva-prezidentskoy-vlasti

[xiv] Guseinov, V. “Aliev after Aliev: Inheritance as a means of retaining power (Алиев после Алиева: Наследование власти как способ ее удержания).” Nezavisimaya Gazeta. 19 March 2004. http://www.ng.ru/ideas/2004-03-19/10_aliev.html

Author: Khursand Khurramov, Political Scientist (Dushanbe, Tajikistan)

The views of the author may not coincide with the position of cabar.asia