Overview of NGOs in Uzbekistan

According to the Ministry of Justice of Uzbekistan the total number of registered non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in the country as of 2020 exceeded 10,000.[1] The Ministry boasted that NGOs are increasingly gaining strong positions in the development of Uzbek society and are becoming a full-fledged partner of the state as the result of adopted legislative measures.

Follow us on LinkedIn

Indeed, since the adoption of the decree of the President, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, in May 2018 a number of positive measures have been taken to ‘radically increase the role of civil society institutions in the process of democratic renewal of the country’.[2] Starting from January 2020 state fees for registration of NGOs, their symbols and representative offices and branches were considerably reduced or lifted with additional privileges for organisations for disabled people, veterans, women and children. The application lead time for NGO registration was reduced from two to one month. Moreover, the Ministry of Justice is developing a web portal, e-ngo.uz, to reduce paperwork and allow registration, reporting (about upcoming NGO events including any trainings/seminars/conferences inside or outside the country, and providing annual reports on the activities of NGOs) and other services for NGOs to take place online.

Being registered as an NGO leads to specific tax benefits particularly if it is an organisation for either disabled people, veterans, women or vulnerable children. The government decided to lift these benefits in the new Tax Code 2020 but under the pressure of civil society activists and the local media the benefits were returned.[3] Importantly, NGO status allows organisations to receive local and foreign grants, and work with international organisations.

The graph shows that there has been a steady increase in the number of NGO registrations in Uzbekistan for the last ten years which almost doubled from 5,103 NGOs in 2009 to 9,338 in 2019. However, can these quantitative changes speak of a quality change and a real breakthrough in the development of civil society in Uzbekistan? Firstly, it is necessary to understand how the figures are calculated and what type of NGOs make up the ostensible positive dynamics. Importantly, the overall number includes all city, district and regional representative offices and branches of NGOs, political parties and trade unions which leads to a multiplier effect. Importantly, a distinction must be drawn between systemic and self-initiated NGOs.[4] Systemic NGOs are government-organised non-government organisations (GONGOs) established by government decrees, directly funded by the state budget and have an extensive network of regional branches.

For instance, before the Women’s Committee of Uzbekistan and the Republican Council for the Coordination of Activities of Citizens’ Self-Government Bodies (the Mahalla Fund) were merged into the Ministry for Support of Mahalla and Family in February 2020 both NGOs counted hundreds of local branches as separate NGOs.[5] As these two systemic NGOs ceased to exist, a possible reduction in the total number of NGOs is expected. Currently, systemic NGOs including their branches account for about 65 per cent of all registered NGOs in Uzbekistan – more than 6000 units.[6]

Struggling with registration of self-initiated NGOs

Another question is whether the quasi-governmental systemic NGOs represent genuine civil society institutions in Uzbekistan. Only about 3000 registered NGOs can be considered as self- initiated by groups of activists which operate at the grassroots level without direct financial support of the government and territorial branches across the country.[7] While systemic NGOs, public organisations and funds of those groups enjoy a close relationship with the government and are easily registered, civil society activists may spend months or even years to do so and face formal and informal barriers when registering their organisations with the Ministry of Justice. Although positive steps are being taken to support civil society in Uzbekistan, the internal administrative procedures of registration for self-initiated NGOs remains bureaucratic, with red tape seemingly designed to frustrate applicants into giving up in the end.

The registering bodies are applying unlawful tactics when reviewing applications which contradict the newly adopted law ‘On Administrative Procedures’.[8] Despite the fact that the review period of the constituent documents was reduced to one month the registration process can be quite lengthy as the judicial authorities do not indicate the full list of shortcomings at first application and keep refusing the NGO registration based on new and vaguely defined mistakes in the organisation’s charter or other founding documents. If necessary, the registering authority has the right to send the application documents to ‘relevant organisations for an expert examination’ which should provide their opinion within 20 days of receiving the documents.[9] However, these ‘expert organisations’ and the criteria for judging registration documents of self-initiated NGOs remain vague and the decisions by third party expert organisations are not usually disclosed to applicants.

The case of an initiative group, a youth volunteer centre, ‘Oltin Qanot’ (Golden Wing) which has been struggling to register as an NGO since October 2018 and has received more than ten refusals from the justice authorities confirms the above mentioned complexities.[10] The initiative group would like to establish an NGO in Tashkent city and has applied to the Department of Justice of Tashkent city, a route deemed easier than registering an NGO at the Ministry of Justice. The reason for the continuous refusals of ‘Oltin Qanot’ can be associated with the monopoly status of the systemic NGO Youth Union of Uzbekistan. The necessity for registration of another youth organisation is most likely questioned by the registering authorities and ‘expert organisations’ as the Youth Union is already in charge of this sphere. Moreover, the Youth Union itself can be listed among organisations which can give their ‘expertise’ on feasibility or usefulness of opening another youth organisation which creates a conflict of interest of a systemic NGO reviewing the registration documents of a potential self-initiative NGO.

The low level of legal literacy amongst initiative groups further complicates the registration process as the Ministry of Justice state they ‘are not entitled to provide legal support in the preparation of constituent documents on state registration of NGOs to counteract the occurrence of a conflict of interests and corruption risks in the judiciary’.[11] While the authorities made sample Charter documents for various types of business entities publicly available and it is now possible to register a commercial company online in 30 minutes via the Single-Window System Centre, self-initiative groups are left behind without any support to facilitate the registration process of NGOs.[12] Although the new e-ngo.uz portal allows online submission of registration documents the internal review procedures remain unchanged. Without officially approved sample NGO Charters grassroots activists are turning to paid services of lawyers which cannot guarantee the correctness of the prepared Charter. The registering bodies can find faults in the constituent documents and reject registration on the basis of the smallest grammatical mistakes or issues with their translation into Uzbek as all the application documents must be submitted in the state language.

Burdensome requirements for notification and prior approval

The lengthy and discouraging process of registering self-initiated NGOs is only the beginning in terms of obstacles. After exhaustive time and money consuming administrative procedures and obtaining the long-awaited certificate of NGO registration, many grassroots civil society organisations are facing other barriers in the process of carrying out their statutory activities.[13] Although the law ‘On Non-Governmental Non-Profit Organisations’ forbids ‘interference by state bodies and their officials in the activities of NGOs’ the Ministry of Justice obliges NGOs to inform them in advance about all planned activities, including conferences, seminars, trainings, meetings, events, roundtables, symposia and other forms of events due to take place in Uzbekistan or overseas.[14] At the same time these burdensome requirements do not apply to political parties and religious organisations which also have NGO status.

For instance, if an NGO plans to hold an event on the territory of Uzbekistan without participation of foreign nationals it should notify the local justice authority at least ten days before the event takes place. If the planned event in Uzbekistan involves foreign citizens or is to take place on the territory of a foreign state – notification should be sent at least 20 days before the event. There is a special notification form consisting of 12 questions to be answered. This form can now be sent online through the e-ngo.uz portal and the information to be provided in advance includes: the theme of the event and the number of participants; the date and the venue; the basis for the holding and sources of funding; attached copies of handouts; print, audio-visual and other materials; as well as personal data of participating foreign citizens. NGOs must also notify officials about all their foreign travel related to the activities of their NGOs and about visits of international guests to Uzbekistan. All above mentioned onerous requirements in practice illustrate direct intervention of the authorities in the activities of NGOs. The justice authorities also have the power to reject or stop activities even if the formal requirements are fulfilled and all necessary documents have been submitted. However, an NGO retains the right to appeal to the court if it is dissatisfied with the decision of the judicial body to ban the event.[15]

Restrictions on foreign funding

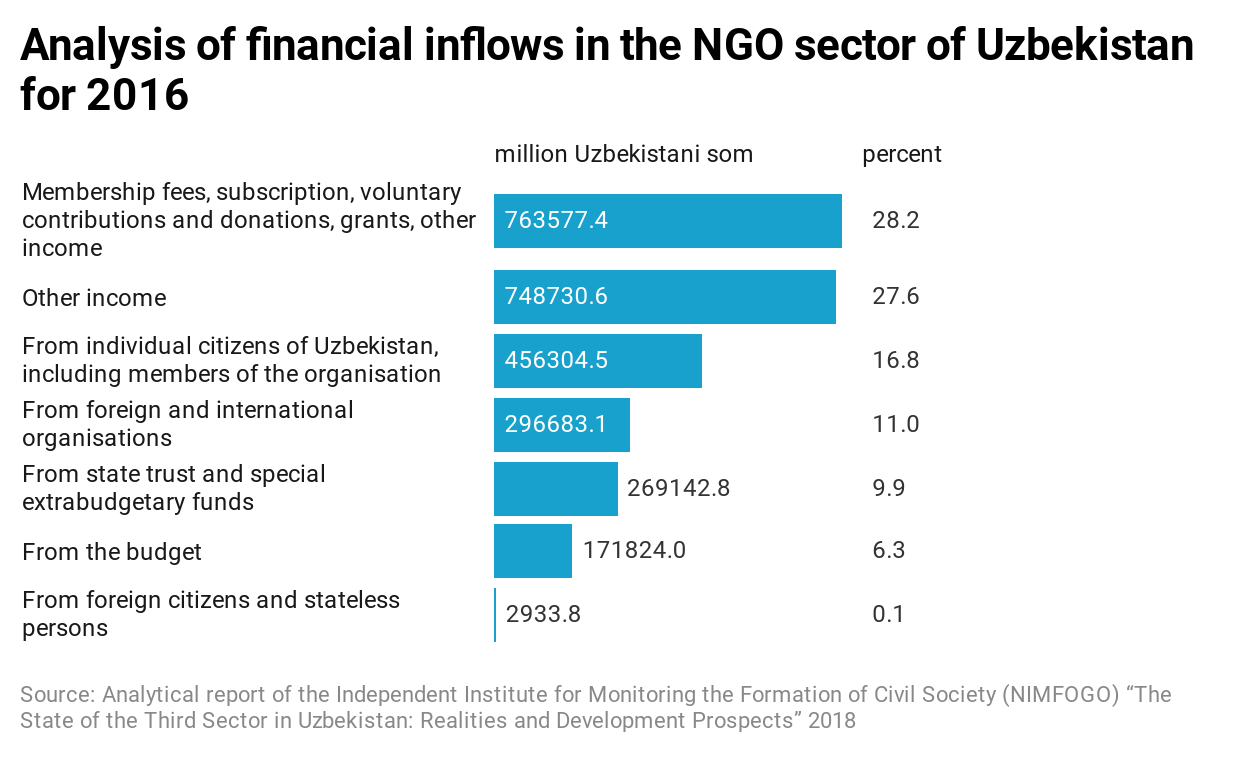

While the financial assistance of the Uzbek government to support the third sector is quite limited barriers are still in place for NGOs to receive grants and other financial support from abroad. The public fund for the support of NGOs and other civil society institutions under the Oliy Majlis is one of the few sources of financial support for NGOs. The diagram below shows the financial flows in the NGO sector of Uzbekistan in 2016. Membership fees and other voluntary contributions account for 28.2 per cent and form the main source of NGOs funding. Importantly, only 11 per cent are funds received from foreign and international organisations while about ten per cent comes from the state trust and extra-budgetary funds.

In his May 2018 decree President Mirziyoyev pointed out that ‘funds allocated by the state to support civil society institutions do not allow the implementation of their medium-term and long-term large-scale and republic-wide projects and programs’.[16] Therefore, the decree outlined the creation of public funds to support NGOs through the allocation of the necessary resources from regional state budgets. Although such public funds were registered in all regions across Uzbekistan, not many of them are actually operating as their funds have not yet been allocated and their staff have not been recruited.

Based on the laws ‘On NGOs’ and ‘On Public Associations’, NGOs are entitled to receive grants and financial support from foreign donors.[17] The Ministry of Justice says that ‘the use of funds and property received by NGOs from foreign states, international and foreign organisations is carried out without any obstacles after agreeing on their receipt with the registration authority’.[18] It should be acknowledged that there have been some alleviations for NGOs to receive foreign grants by opening a grant account at any bank in Uzbekistan. Before NGOs would have had to open special accounts at only two banks, the National Bank for Foreign Economic Affairs of the Republic of Uzbekistan or the state-owned joint-stock commercial bank Asaka where a so-called special ‘grant commission’ carried out evaluations of received grant funds based on unwritten rules and criteria.

In October 2019 the Cabinet of Ministers of Uzbekistan approved a new regulation on the procedures for coordination of the money and property received by NGOs from international donors. According to the decree signed by the Prime Minister of Uzbekistan Abdulla Aripov, if the amount of foreign cash and property received by an NGO within one calendar year does not exceed 20 ‘basic calculation values’ (4,460,000 Uzbekistani Som as of February 1st 2020), then the documents are submitted to the Ministry of Justice for information. If the amount exceeds this, documents must be submitted for approval.[19] Considering that 20 BCV in one calendar year is a minor amount (about 450 US dollars), for many NGOs relying on foreign funding coordination means getting approval. Furthermore, the Ministry of Justice retains the right to reject receipt of foreign funding if the funds are found to ‘jeopardise [the] health and moral values of citizens’.[20] Taking into consideration the vague nature of the concept of ‘morality’, which is not legally defined, this provision can be used by the authorities to refuse foreign funding for NGOs.

Low organisational capacity of self-initiated NGOs

Due to the limited financial support from the government and existing barriers on international funding self-initiated NGOs, unlike systemic GONGOs, do not have sufficient organisational capacity and resources. This was also confirmed by the presidential decree from May 2018 recognising that ‘the state of material and technical support of non-governmental non-profit organisations is still unsatisfactory’. One of the biggest problems self-initiated NGOs are facing is the inability to rent office spaces to carry out their activities. About 80 per cent of NGOs do not have their own premises, particularly in the remote regions.[21]

Based on the decree the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Karakalpakstan, hokimiyats (local government) of regions and the city of Tashkent, together with the State Committee for the Promotion of Privatised Enterprises and the Development of Competition, had to create ‘houses of NGOs’ based in empty or inefficiently used state property in all regions of Uzbekistan until January 1st 2019. Nevertheless, only three ‘house of NGO’ were created throughout the republic – one in Urgench, where only 19 NGOs were provided with office space, one in Gulistan, where 12 NGOs found shelter, and one in Nukus. The office spaces in the ‘houses of NGOs’ should be primarily allocated to newly established NGOs in socially significant areas at a ‘zero’ rental rate. However, there are doubts that this will be enforced, and that preference will be given to systemic GONGOs rather than self-initiated grassroots organisations. The creation of several NGO houses in each region may not be a feasible solution as there will be not enough for the estimated 3000 self-initiated NGOs.

Centralisation of charity activity during the COVID-19 pandemic

The first case of COVID-19 was registered in Uzbekistan on March 14th and on the same day the Uzbek government announced the shutting down of schools, colleges and universities.[22] Subsequently the Tashkent government introduced strict quarantine measures step-by-step: banning and introducing penalties for walking in public without PPE, closing all border checkpoints, prohibiting weddings and other public gatherings, cancelling all domestic flights and railways, suspending public transport, putting restrictions on using private vehicles, etc.[23] Despite these strict measures the initiative to support vulnerable groups (elderly, disabled and low-income families) came from volunteers and grassroots civil society activists that used social networks (Telegram and Facebook) to distribute help to those in need.

However, on April 1st Elmira Basitkhanova the former chairperson of the systemic NGO Women’s Committee of Uzbekistan who was appointed first deputy Minister for Mahalla and Family Affairs announced in public that in five days 200 complaints were received about the delivery of food to the elderly and low-income families by volunteer groups.[24] She backed up her argument to curb volunteer efforts asking whether donating to elderly people who are at higher risk of contracting the coronavirus is a violation of quarantine requirements, questioning how their safety is ensured and who controls the quality of delivered products. Therefore, on April 1st the Sponsorship Coordination Centre was established under the Ministry for the Support for Mahalla and Family with a single short number 1197.[25] It was recommended to transfer all donations to a systemic public foundation with an NGO status, ‘O’zbekiston mehr-shafqat va salomatlik’ (Uzbekistan – mercy and health), which was established by the Government of Uzbekistan in November 28, 1988 at a conference in February 1989 and re-registered by the Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Uzbekistan on November 21st 2014.[26] Thus, the Uzbek government centralised and monopolised charity allocation through a single government-organised public fund and the Sponsorship Coordination Centre while the activities of volunteer groups and civil society organisations were restricted.[27]

Moreover, on April 20th President Mirziyoyev proposed the creation of another systemic NGO fund, ‘Saxovat va ko’mak umumxalq harakati’ (nationwide movement ‘Generosity and Assistance’), suggesting that businessmen and entrepreneurs should transfer their donations to the fund to actively support vulnerable members of population in their local mahallas during the period which coincided with the holy month of Ramadan.[28] The businessmen who donated to the fund were promised by the president they would receive various benefits (e.g. taxes concessions, access to leasing, credits and other resources) depending on the level of assistance and support they provided. Rather than resorting to ‘helicopter money’ Mirziyoyev decided to provide social protection via his appeal to businesses and entrepreneurs.[29]

Due to the lack of transparency and accountability of the state-organised funds there were several cases of violations and crime related to the appropriation of donated funds. For instance, a deputy mayor (Khokim) in the Akkurgan district who was the head of the district department for mahalla and family affairs misappropriated charitable funds from the ‘Mahalla’ fund and ‘Saxovat va ko’mak’ fund. The Prosecutor’s Office have opened a criminal case under Article 167 (theft by embezzlement) of the Criminal Code.[30] In another investigative report it was found that the activities of the state-owned charity fund ‘Saxovat and ko’mak’ contradicts the laws of Uzbekistan, which prohibits the government to create such foundations.[31] Moreover, the journalist found that the fund purchased products at inflated prices, and its account was replenished through ‘voluntary’ random deductions from the salaries of employees of state organisations.

Apart from the embezzlement of public funds, the top down approach to charity allocation has had negative impacts on the most vulnerable segments of Uzbek society. Firstly, the centralisation of aid allocation in the form of a single Centre and single emergency hotline considerably increased the transactions costs to review each application, which was quite difficult in the absence of any eligibility criteria and lack of a single database of children and adults in need of social protection. The one-size-fits-all approach with a fixed bundle of basic goods did not really work as the people had unique needs. As a result, many people who needed help were not able to reach the hotline on the phone and were left behind.

Social partnership and trust of the government in volunteer groups and civil society organisations rather than the monopolisation of charity activities via government-organised public funds would have been a more effective and efficient response to the needs of the vulnerable amid strict COVID-19 quarantine measures. Compared to systemic GONGOs, self-initiated NGOs and civil society groups already had an extended network of beneficiaries at the grassroots levels and a better understand of the needs of their members. Therefore, the transaction costs and time they use to distribute goods and services might be lesser. Importantly, if the Uzbek government had cooperated with such NGOs the staff and volunteers could have been supported and remunerated for their charity work thus being able to sustain their families as well through the crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic should have been used an opportunity to develop the organisational capacity of self-initiated NGOs to make them more resilient for future crises.

Strict controls rather than equal partnership

In March 2020 the registration of a human rights NGO Huquqiy Tayanch (Legal Support), the first since 2003, has sparked some hope for further liberalisation of the third sector in Uzbekistan.[32] Despite this successful single case and the recent easements in the formal registration and regulation requirements of NGOs in Uzbekistan tightly controlled measures are still in force. The sector is in need of systemic changes to provide freedom of association and to develop models of equal social partnership.[33] Persistent stereotypes and prejudices towards independent NGOs prevail, with a lack of trust and negative attitudes towards NGOs, sometimes seen as ‘foreign agents’ by the Uzbek government and society may further hinder the reforms that are vital to strengthen the capacity of self-initiated NGOs.[34]

On April 16th 2020 the Public Chamber under the President was created with the main objective to establish a dialogue between the state, citizens, and civil society institutions.[35] The Public Chamber can organise public hearings, examine draft laws and regulations, and monitor and prepare annual national reports on the state of civil society in Uzbekistan. However, as not all of its members are elected, with 18 out of the 50 members appointed by the president, there are doubts that the Chamber will be truly public and independent and that it may turn into another state Chamber.[36]

Currently, the Ministry of Justice together with civil society activists are working on a new NGO code which should become a touchstone to develop a genuine and vibrant civil society in Uzbekistan. However, the working group should have submitted a draft of the NGO code to the Cabinet of Ministers by February 1st 2020. This is not the first delay, with several deadlines missed already.[37] To make it happen the authorities are advised to follow these recommendations:

- Improve data collection practices on NGOs and make their financial data publicly available for researchers and those interested in independent assessment and evaluation of the third sector development;

- Make the registration process of self-initiated NGOs transparent and easy in the interest of grassroots initiative groups, provide legal support and samples of Charter documents to avoid shortcomings in the application documents and to facilitate their swift processing;

- Provide financial and organisational support to self-initiated NGOs and other civil society institutions through state funds and other means of support by encouraging local public and philanthropic fund-raising activities;

- Restrict unlawful state intervention in the activities of NGOs through burdensome requirements for reporting and advance approval for the day-to-day activities of NGOs; and

- Lift limits on foreign funding of NGOs and other administrative barriers to their international contact.

Dilmurad Yusupov is doctoral researcher at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS), University of Sussex. He can be followed on Twitter @d_yusupov.

This material has been prepared as part of the Foreign Policy Centre’s Spotlight on Uzbekistan publication edited by Adam Hug. The opinions expressed in the essay do not reflect the position of the CABAR editorial board.

[1] Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Uzbekistan, Refusal to register NGO: causes and the consequences, January 2020, https://www.minjust.uz/en/press-center/news/98816/

[2] Decree of the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan, On measures to radically increase the role of civil society institutions in the process of democratic renewal of the country, LexUZ, dated May 2018, http://lex.uz/docs/3721651

[3] Dilmurad Yusupov, Uzbekistan’s Tax Code 2020: no benefits for charities, March 2020, https://dilmurad.me/uzbekistans-tax-code-2020-no-benefits-for-charities/

[4] Dilmurad Yusupov and Oybek Isakov, Why is it Difficult to Open an NGO in Uzbekistan?, CABAR.asia, January 2020, https://cabar.asia/en/why-is-it-difficult-to-open-an-ngo-in-uzbekistan/

[5] UZDaily, Mahalla and Family Support Ministry established in Uzbekistan, February 2020, https://www.uzdaily.com/en/post/54895

[6] Analytical report ‘The state of the “third sector” in Uzbekistan: realities and development prospects’, Independent Institute for Monitoring the Formation of Civil Society (NIMFOGO), 2018.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Leonid Khvan, Legislatively about administrative procedures and registration of NGOs, Gazeta.uz, February 2020, https://www.gazeta.uz/ru/2020/02/14/administrative-procedures/; Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan, On Administrative Procedures, dated January 2018, No. ZRU-457, LexUZ, https://lex.uz/docs/3492203

[9] Decree of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Uzbekistan ‘On measures to implement the resolution of the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan dated December 12, 2013 No. PP-2085 ‘On additional measures to assist the development of civil society institutions’, LexUZ https://www.lex.uz/acts/2356874#undefined

[10] Dilmurad Yusupov and Oybek Isakov, Answer to the Ministry of Justice about the problems of registration of NGOs, Gazeta.uz, February 2020, https://www.gazeta.uz/ru/2020/02/12/answer/

[11] Ministry of Justice, Denial of registration of NGOs: causes and consequences, Gazeta.uz, January, 2020, https://www.gazeta.uz/ru/2020/01/28/mj/

[12] Business Entity, Registration Module of the EITI Portal, https://fo.birdarcha.uz/s/uz_landing

[13] Yusupov and Isakov, Regulations of NGOs: Control of Partnership?

[14] Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan, ‘About Non-Governmental Non-Profit Organizations’ dated April 14, 1999, LexUZ, https://www.lex.uz/acts/10863; Order of the Justice Minister of the Republic of Uzbekistan, ‘On approval of the regulative procedure for notification of planned activities of non-governmental non-profit organizations’ of June 1, 2018, LexUZ, https://www.lex.uz/acts/3776151#3776168

[15] Decree of the Minister of Justice of the Republic of Uzbekistan, ‘On Approval of the regulation and procedures of notification of planned activities non-government non-profit organisations’, dated June 1, 2018, LexUZ, https://www.lex.uz/acts/3776151#3776168

[16] Decree of the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan, ‘On measures to radically increase the role of civil society institutions in the process of democratic renewal of the country’, dated May 4, 2018 No. UP-5430, http://lex.uz/docs/3721651

[17] Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan, ‘On non-government non-commercial organisations’, dated April 14, 1999, LexUZ, https://www.lex.uz/acts/10863; Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan, ‘On public associations in the Republic of Uzbekistan’, dated February 15, 1991, LexUZ, https://www.lex.uz/acts/111827

[18] Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Uzbekistan, Refusal to register NGO: causes and the consequences, MinJust, January 2020, https://www.minjust.uz/en/press-center/news/98816/

[19] Decree of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Uzbekistan, ‘On approving the procedure for accepting the receipt of funds by non-governmental non-profit organizations from foreign states, international and foreign organizations, citizens of foreign states or, on their instructions from other persons’, dated October 9, 2019, LexUZ, https://lex.uz/ru/docs/4546607

[20] Ibid.

[21] Yusupov and Isakov, Regulations of NGOs: Control of Partnership? https://cabar.asia/en/regulation-of-ngos-in-uzbekistan-control-or-partnership/

[22] Olzhas Auyezov, Uzbekistan confirms first coronavirus case, closes schools, borders, Reuters, March 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-uzbekistan/uzbekistan-confirms-first-coronavirus-case-closes-schools-borders-idUSKBN21206W

[23] Gazeta.uz, The month that has changed Uzbekistan, April 2020, https://www.gazeta.uz/ru/2020/04/15/chronicle/

[24] Kun.uz, Elmira Basitkhanova appointed to a new position, February 2020, https://kun.uz/en/news/2020/02/20/elmira-basitkhanova-appointed-to-a-new-position; Anora Ismailova, Elmira Basithanova said that in five days there were about 200 complaints about the delivery of food to elderly people and low-income families, Podrobno.uz, April 2020, https://podrobno.uz/cat/obchestvo/elmira-basitkhanova-zayavila-chto-za-pyat-dney-postupilo-okolo-200-zhalob-na-rabotu-volonterov-dosta/

[25] UZDaily, Sponsorship Coordination Centers to start operating in Uzbekistan, April 2020, http://www.uzdaily.com/en/post/55794

[26] Mercy and Health Community Foundation, https://mehrshafqat.uz/

[27] Dilmurad Yusupov, How COVID-19 is affecting disabled people in Uzbekistan?, Dilmurad.me, April 2020, https://dilmurad.me/how-covid-19-quarantine-is-affecting-disabled-people-in-uzbekistan/

[28] Fergana News, “Generosity and Assistance”, April 2020, https://en.fergana.news/articles/117489/

[29] Eurasianet, Uzbekistan: President nixes helicopter money idea, appeals to business community, April 2020, https://eurasianet.org/uzbekistan-president-nixes-helicopter-money-idea-appeals-to-business-community

[30] Kun.uz, Deputy khokim misappropriated charitable funds in Akkurgan district, May 2020, https://kun.uz/en/news/2020/05/18/deputy-khokim-misappropriated-charitable-funds-in-akkurgan-district

[31] Mirzo Subkhanov, Uzbekistan: charity with violations, CABAR.asia, May 2020, https://cabar.asia/en/uzbekistan-charity-with-violations/

[32] Eurasianet, Uzbekistan sparks hope with registration of NGOs, March 2020, https://eurasianet.org/uzbekistan-sparks-hope-with-registration-of-ngos

[33] The Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan, ‘On Social Partnership’, dated September 25, 2014, Lex.Uz, https://www.lex.uz/docs/2468216

[34] Nikita Makarenko, Maidan-Paranoia, Gazeta.uz, January 2020, https://www.gazeta.uz/ru/2020/01/31/ngos/; Referencing the 2013/14 protests in Ukraine that led to the overthrow of its Government; Gerard Toal, John O’Loughlin and Kristin M. Bakke, Are some NGOs really “foreign agents”? Here’s what people in Georgia and Ukraine say, openDemocracy, April 2020, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/are-some-ngos-really-foreign-agents-heres-what-people-georgia-and-ukraine-say/

[35] Decree of the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan, ‘On the Creation of the Public Chamber under the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan’, April 16, 2020, uza.uz, https://uza.uz/ru/documents/o-sozdanii-obshchestvennoy-palaty-pri-prezidente-respubliki–17-04-2020

[36] Sanjar Saidov, Uzbekistan: Public of State Chamber? CABAR.asia, May 2020, https://cabar.asia/en/uzbekistan-public-or-state-chamber/

[37] Gazeta.uz, NGO code will be developed in Uzbekistan, October 2019, https://www.gazeta.uz/ru/2019/10/05/ngo/