“If Uzbek language is the state language, first of all, it is needed to “create” this language, “unitize” and introduce into scientific circulation. The actual absence of Uzbek language in science and art impedes its development as a national one”, – notes an independent researcher Bakhtiyor Alimdjanov in his article written specifically for the analytical platform CABAR.asia.

Русский ЎзбекчаFollow us on LinkedIn

Summary of the article:

- High ranking government officials of Uzbekistan speak the state language very poorly. The fact that the entire Uzbek elite got education in Russian and worked in the Soviet government institutions is the main reason for this linguistic phenomenon;

- Non-involvement of Uzbek in the world “modernization” processes has turned it into language of “plain folk”;

- Russian is a sacred political language for the population of Uzbekistan;

- A stalled alphabet reform leads to the coexistence of two alphabets in everyday life and education;

- Knowledge of Russian has become a sign of belonging to a special privileged caste;

- Despite all the difficulties, Uzbek language is preserved in cinema, theater and music;

- Internet and local segments of social networks remain the last “island” of Uzbek language development.

Uzbekistan’s “Oliy Majlis” Senate Chairman, Nigmatilla Yuldashev stated at a meeting of the upper house of parliament on December 13, 2018 that the implementation of law “On the state language of the Republic of Uzbekistan” was left to the mercy of fate[1]. This statement shows that there is a growing need to use Uzbek as a language of power in Uzbekistan. Reasonable questions arise in regard of this situation: how can Uzbek become truly national or state language? What is the role of Russian language in the Uzbek modern society? Is there a purposeful state language policy?

Whose Uzbek language?

Joseph Brodsky wrote: “Language of the nation is the best what the nation has.” Uzbek language has not become a language of power over the past 28 years. Top ranking government officials of Uzbekistan speak on the state language very poorly. They prefer to quality speak in Russian. The middle and lower echelons of the bureaucratic class tolerably speak Uzbek, using many dialectisms and europeanisms. In terms of the language, metropolitan middle bureaucracy is not very different from the provincial one. Most likely, provincial ones are less “aggressive” in the language aspect and more “national”. The fact that the entire Uzbek elite got education in russian language and worked in the Soviet government institutions is the main reason for this linguistic phenomenon. Despite the “power” of Russian language in the state structures of Uzbekistan, the workflow in Uzbek language has been growing in recent years. Some politicians urge to translate all record management into Uzbek language. It becomes clear that it is difficult to expect a shift in this area when the central executive authorities and parliament of the republic actively use Russian for record management. The local administration in provinces uses Uzbek, but resort to the Russian language when a serious report needs to be sent “upward”. The fact that higher authorities do not know Uzbek language is obvious. But it is impossible to solve state affairs in national “non-modern” language even if they know it at trivial level. The use of the Russian language in parliament also has its justification. The juristic Uzbek language has not developed. There are no good textbooks in Uzbek yet. Since Uzbek was not formed into a “modern” and understandable language it is impossible to use it as a legal and political. Is Uzbek an “anti-modernization” language? Non-involvement of Uzbek in the global “modernization” processes has turned it into language of “plain folk”. The society has an opinion that talking about serious things in national language is impossible. It must be stated that the process of language decolonization has not occurred, i.e. Uzbek has not become a modernization language.

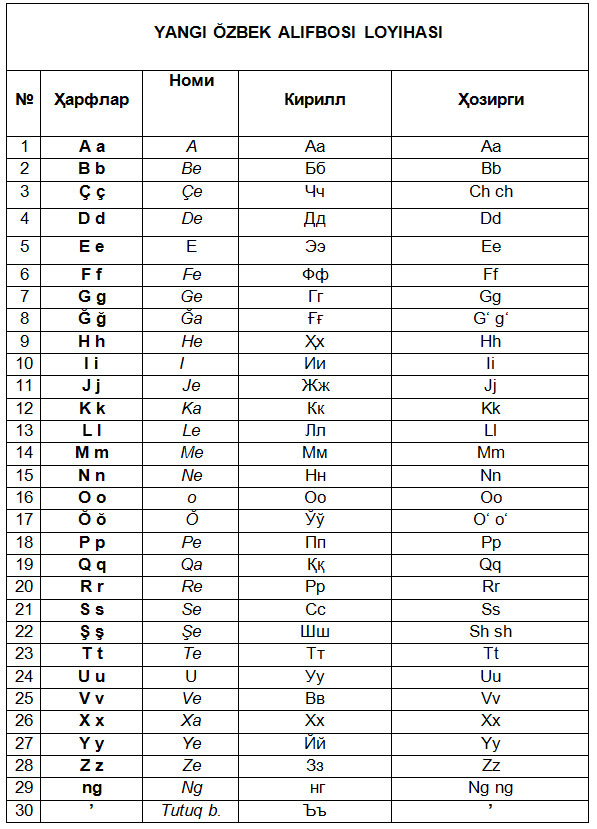

In May 2018, the government of the republic re-launched the Latinic reform[2]. The authorities decided to approve a new version of Latinic before the end of 2018. New Latinic strongly resembles the Latinic version of 1993 (the “Turkish” version). According to experts, the “new” version of the Latin alphabet “will bring the alphabet closer to the alphabets of other Turkic languages”. We come back again to the national ideology of the 90s of the XX century – to the idea of Turkic languages unity!

According to experts, the reforms of the alphabet are connected with the foreign policy of Uzbekistan. Uzbekistan was moving closer with Turkey and the United States in the 90s of the 20th century, and from the second half of the 2000s – with Russian Federation. Foreign policy games partially influenced the language situation in Uzbekistan. The failure of the alphabet reforms had a negative impact on Uzbek language. It could not become a modern language of a young state. Ignoring Uzbek in society and perceiving it as a “non-fashionable” language, created an absence of demand effect for Uzbek as a modernizing communication. Learning English also “impeded” the development of Uzbek. Uzbek language seemed to be “frozen” in time and became a language tool and a sign of “underdevelopment”.

Russian language as a sign of elitism

A new Tashkent State University of Uzbek Language and Literature under the name of Alisher Navoi was founded by the decree of the first president, I.A. Karimov, dated May 13, 2016. The main task of the university was an “enhanced study and development of Uzbek language and literature.” An Uzbek-English translation department was also established at the university. An internal and foreign policy of Uzbekistan has changed with the coming of Sh.M. Mirziyoyev to power. In December 2017, Sh.M. Mirziyoyev visited this university and instructed the students: “You should show the diversity of our native language, respect and love for it through its wide distribution throughout the world”[3]. In 2018, a turkological center was opened at the university, where the “new” alphabet is being developed.

Russian language influence the republic may be increased by active diplomatic and trade relations between Tashkent and Moscow, as well as the visit of V.V. Putin in October 2018. During the October meetings, Sh.M. Mirziyoev ordered to publish one hundred volumes collection of Russian classics works in Uzbek language. We hope that translation of Russian classics into Uzbek (although this was done in the last century) and translation of Uzbek classics into English will become a catalyst for the development of Uzbek as a national and state language. Uzbek language and internet Internet and local segments of social networks remain the last “island” of Uzbek language development. Uzbek-language news agencies kun.uz, daryo.uz, Turon24 and foreign broadcasts “Voice of America” and Russian “Sputnik” in Uzbek language create a competitive market on Facebook and Instagram. “Different” Uzbek languages are spoken in these news agencies. There are no unified terms, what sometimes leads to misunderstandings and verbal arguments among the information consumers. Blind imitation of Western patterns leads to the import of many foreign words that are not yet rooted in Uzbek everyday life. Dictionary of Uzbek language is being artificially modernized. It is not connected with actual situation and does not reflect the reality. Sometimes it seems that the language of Uzbek-language media is essentially translational; not from Russian, but from English. The situation turns out “from bad to worse”. We need such Uzbek that would reflect the reality based on the capacity of our language. What language policy does Uzbekistan need? English and Russian are actively learned in the republic now. Uzbek language is becoming a language of world classics translation, i.e. the “dead” language. Uzbek language is subject to manipulation by the efforts and statements of some politicians who are trying to earn points on the political arena. If Uzbek is the state language, first of all it is needed to “create” this language, “unitize” and introduce into scientific circulation. The actual absence of Uzbek language in science and art impedes its development as a national one. The state needs to precisely define the “modernization” ideology not within the framework of the existing “internal colonization”, but the decolonization of culture, which starts with language. Does Uzbek language have a future? Uzbek should become modern, national and really state language of Uzbekistan. It should be borne in mind that the existing situation can only be changed by an integrated approach to Uzbek language. The national “rescue” program of Uzbek language should include the following items:- Uzbek language “reconstruction” at the national level requires huge investments, i.e. no need to spare money;

- We need specialists, not only philologists, but also historians, orientalists, lawyers and mathematicians for the joint development of the modern scientific Uzbek language – they need to be prepared and adequately paid for their work;

- It is necessary to unify the language of art (cinema, theater, music) and clear it of dialectisms, jargon and neologisms;

- It is necessary to stimulate literature in the national language by free publication of new authors’ books;

- “Flood” the Internet, especially social networks by the new Uzbek “dialect” – the state language.

And the most important thing is to encourage all school teachers and educators of the republic to speak and write in accordance with the norms of the state Uzbek language. School, university and art in tandem should become a driving force of the new modernized “normal” Uzbek state language.

[1] Nigmatilla Yuldashev stated that Uzbek language is disrespected in the country.Kun.uz (appeal date 12/21/2018). [2] Nigmatilla Yuldashev stated that Uzbek language is disrespected in the country.Kun.uz (appeal date 12/21/2018). [3] The President visited Tashkent University of Uzbek language and literature. Kommersant.uz (appeal date 12/21/2018).This article was prepared as part of the Giving Voice, Driving Change – from the Borderland to the Steppes Project implemented with the financial support of the Foreign Ministry of Norway. The opinions expressed in the article do not reflect the position of the editorial or donor.