“It must be recognized that the problem of human trafficking is not conventional for Kyrgyzstan in the sense that the authorities do not fully understand what means and methods must be used to deal with, prevent, and detect these crimes,” – expert Atai Moldobaev, writing specially for cabar.asia, uncovers important aspects of the problem of human trafficking.

Follow us on LinkedIn!

Before characterizing the problem, one must first of all note that human trafficking is a gross violation of basic human rights, threatens personal freedom, health, and security.[1] Approaches to solving the issue originated in the twentieth century with recognized legal acts enshrined in international law, which defines today’s scope, thus creating the rules and mechanisms for combating human trafficking.

Before characterizing the problem, one must first of all note that human trafficking is a gross violation of basic human rights, threatens personal freedom, health, and security.[1] Approaches to solving the issue originated in the twentieth century with recognized legal acts enshrined in international law, which defines today’s scope, thus creating the rules and mechanisms for combating human trafficking.

Figures for Central Asia

The involvement of a large number of stakeholders shows the high relevance of the problematic issue, as well as the urgent need for an adequate response to a challenge of our time. Human trafficking today is a vast niche in the world of shady business with an annual turnover of about US $150 billion[2], and the major share of global turnover comes from Eastern Europe and the CIS.[3] Central Asian countries are no exception. The main areas of operation in the region are for domestic agricultural services, construction, sexual slavery, and child labor, as well as conveying recruits to war zones in the Middle East. In addition, the nature of human trafficking in the region varies in each country where the socio-economic level of the republic appears as a key factor and determines the extent of the problem.

For example in 2015, per capita GDP in Kazakhstan amounted to US $25,044, Turkmenistan – $16,532, Uzbekistan – $6,086, Kyrgyzstan – $3,433.6, and Tajikistan – $2,833.[4] Macroeconomic performance directly correlates with the level of human trafficking. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are to a lesser extent transit and more destinations whereas all the other republics of the region are transit points and the countries of origin for human resources. In considering this statement, it becomes obvious that the vulnerable segments of human trafficking are foreign and internal migrant workers and disadvantaged sections of the population such as women and children.

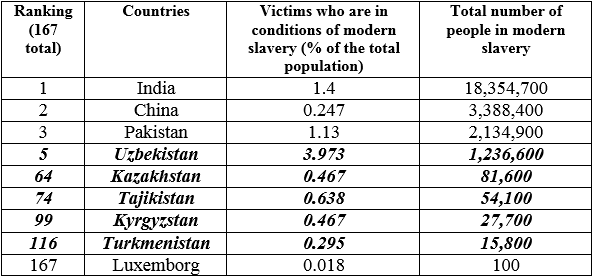

According to the ranking of countries by the number of people in slave-like conditions, The Global Slavery Index, which is compiled by the Australian Human Rights Foundation “Walk Free Foundation”, states the regional situation is as follows:

Table 1: Total number of enslaved people by country[5]

Taking into account these figures, regional statistics of solved trafficking crimes remains low, as well as the potential for Central Asian countries to combat human trafficking. For example, according to the US State Department’s report on human trafficking for 2016 and Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs’ official statistics for 2015, only 92 cases of human trafficking were opened. Here it should be noted that 77 cases were related to sexual slavery while the other 15 dealt with forced labor.[6] There is also the fact that only two of the slavery victims were from abroad. However, these figures need to be considered as significantly underestimated since the newsfeeds of several media outlets reveal that migrant workers from neighboring countries are victims of slavery much more frequently.[7]

In Uzbekistan, police claim that 696 investigations were conducted and 372 cases were prosecuted on charges of human trafficking. For 2015, 924 victims of the crimes of human trafficking were registered but only 140 were victims exploited on Uzbekistan’s territory.[8] Only 146 victims were provided diplomatic support by authorities for repatriation, and the remaining workers stayed on in neighboring countries. Overall, these figures suggest that the overpopulation of certain areas of the country, low socio-economic level of the non-urban population, as well as high-value agriculture provide an attractive business for regional organized crime in Uzbekistan concerning both transit and forced operation within the state.

Tajikistan, which is increasingly a country of origin, has more modest statistics with 25 criminal cases investigated, involving 39 suspected traffickers.[9] A similar situation exists in Turkmenistan where there were 12 victims in 2015.[10] It should be noted that the specificity of the political regime of Turkmenistan does not allow a full analysis by international NGOs so there is no real data.

The problem of human trafficking in Kyrgyzstan

The data for Kyrgyzstan, according to the same report, is different. The General Prosecutor’s Office claims there were 62 victims of trafficking whereas international NGOs declare 192 victims in 2015, the bulk of which were used in forced labor and the sex industry. According to the Eurasia Foundation of Central Asia, there are no less than 5,000 cases of human trafficking annually in Kyrgyzstan.[11]

According to statistics from Kyrgyzstan’s State Migration Service, 10 criminal instances were recorded with one remaining unsolved. The most common circumstance of trafficking, according to the source, is the sale of babies.[12] Social workers say that in Kyrgyzstan it is easier to “buy” a child than to adopt one as national law complicates the adoption process at times.[13] Interested persons in this manner find ways around government procedures, which are known to cost and require additional finances for their acceleration. In this case, it is clear that in spite of the criminality and the high moral responsibility, today there is a tendency for a kind of “market” in which the most valuable commodity is considered to be newborns. The cost ranges from 20-25,000 soms[14] to US $7,000[15] depending on the region and the conditions of women in labor. The most egregious case in Kyrgyzstan is the sale of children’s organs with one in particular occurring in the past year. A stepfather, after the death of his wife, sold the children for organs.[16] A high level of labor migration exacerbates the situation when one parent travels abroad for work, which makes it possible to sell their baby to another.

It should be noted that Kyrgyzstan, due to its domestic political objectives and socio-economic factors, is a provider of human resources not only for CIS countries (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Russia, China), but also for those further afield (South Korea, Finland, UAE, Turkey, India, and et al.). The International Organization for Migration says that about 15,000 Kyrgyzstani citizens become victims of human trafficking in foreign countries.[17] Organized crime Kyrgyzstan, which, by the way, occupies a rather strong position not only in the region but in the whole post-Soviet space, plays an important role in this process. Kyrgyzstani criminals have coalesced into separate independent groups (e.g. in Moscow) and given that they do not pose to be powerful forces in Russia the main focus of their activities are placed on their own compatriots.[18]

Migrant workers are subjected to paying tribute and in cases of delinquency are forcibly exploited by criminal elements involved in heavy manufacturing. Favorable terms can have the “debtors” sold to work in the underground shop, construction, etc. The shady scheme, with a good amount of money based on one person, as well as the high level of corruption provide a basis for the involvement of criminals and unscrupulously corrupt civil servants in order to achieve a guaranteed uninterruptable business.[19] Thus, the detection of illegal actions is hindered at times and allows brokers to expand their activities. The most active area of trafficking is the southern region of the country, in which about “80% of the population are involved in labor migration” and, therefore, more at risk of being exploited.[20]

Meanwhile, the preventive measures taken by the government for initiatives and programs to combat human trafficking have not brought about the desired results. Examples of these initiatives would be the Law “On Preventing and Combating Trafficking in Human Beings” (From 14.01.2013 №14), the Criminal Code of the Kyrgyz Republic, and other normative-legal acts.[21] This failure is reflected, primarily, in the legal framework’s imperfections, which leads to the fact that proving instances of human trafficking is becoming increasingly difficult in Kyrgyzstan today. There are no “approved criteria for identifying victims of trafficking” and there are no clear functional differentiations to combat human trafficking.[22] These shortcomings pose some difficulty for government agencies to respond to, as well as the classification of crimes and offenses. In addition, each agency responds to cases of human trafficking in accordance with their competencies thus leading to a lack of coordination between government agencies. Thus, “the Interior Ministry announced 10 instances of slave trade, the Foreign Ministry said there were more than 30, and the International Organization for Migration said there were around 174 victims of sexual and labor slavery”.[23] Therefore, inter-agency coordination is regarded as an urgent necessity in countering the problem of human trafficking.

Another weak spot and probably the most dangerous is the complex social problem of stung sectors of society. It is no secret that the failure to obtain a secular education is due to objective reasons (inaccessibility of schools, the need to work, low motivation to acquire knowledge, etc.). Youth then seek to fill this vacuum by trekking to the mosque, where because of their weak critical thinking, are victimized recruits of various religious sects. At the same time, to assert that “preying” emissaries of religious organizations target only rural youth is unfair as urban spaces and mechanisms for recruitment (online platforms, friends, high concentration of religious sects, mosques, lack of goals and values in some segments of the youth, etc.) are much more prolific. This is largely supported by the low education of imams in small and medium-sized mosques and madrassas along with the weak capacity for preventive work among his flock and students prone to radicalization.

In addition, around 99 madrassas in Kyrgyzstan operate without any authorization or registration, which gives reason to believe that they are involved with banned religious sects and student recruitment.[24] In many ways, this is the result of weak state control and the reasons for the recruiting and trafficking of young people, which is mainly for sending them to combat zones in the Middle East, particularly Syria. As it is known, according to the Kyrgyz State National Security Committee, around 600 people have left for Syria from Kyrgyzstan since 2013 with most of them being natives from the southern regions of the country.[25] Their return to Kyrgyzstan, as well as the experience of fighting, creates some space not only for the development of radical ideas in the country but also to send to other people to Syria thus exacerbating the problem of trafficking in Kyrgyzstan.

It must be recognized that the problem of human trafficking is not conventional for Kyrgyzstan in the sense that the authorities do not fully understand what means and methods must be used to deal with, prevent, and detect these crimes. As a result, the main tool in the fight against human trafficking is the prevention, notification, and targeting of vulnerable at-risk groups who more often become the victims of forced labor and modern slavery. Opening support centers and hotlines (such as service “189” which was opened with the support of the International Organization for Migration), conducting trainings, and providing capacity building for civil servants and law enforcement agencies, as well as workshops and events to raise awareness among the population, could help greatly. Especially important, in our opinion, would be for the GKNB to contribute by showing the real-world experience of ISIL and Syrian opposition combatants in the first person at seminars and warning young people who desire to travel to Syria. NGOs also play a very important role. In contrast to their participation on rather controversial political issues to solve this problem, they are regarded as one of the successful elements that can provide the means to work with various sectors of society and the sheer volume that the state cannot physically reach.

Recommendations

Accordingly, it should be noted that it is necessary to take the following measures to improve the effectiveness of combatting human trafficking and other forms of modern slavery:

- Adoption and implementation of a long-term strategy to prevent trafficking in Kyrgyzstan while uniting the efforts of all the various state agencies.

- The introduction of special legal norms and instruments (for example, the criteria for identifying victims of human trafficking) in the country’s legislation in order to improve the regulatory framework.

- Raise awareness among the population, including educational events at schools, universities, state agencies, religious communities, and remote locales.

- Focus activities in the south of the country and in the regions.

- Expansion of NGOs and international organizations in this direction.

- Toughen criminal penalties under articles suitable for prosecuting human trafficking.

- Conduct social awareness campaigns and activities on a constant basis.

- Creation of a special database, which would take into account all socio-economic indicators of trafficking victims to further identify patterns and then work on the causal phenomena.

In many ways, it should be understood that the problem of human trafficking runs deep into other aspects of life such as education, socio-economic level, quality of life, and other factors. For Kyrgyzstan, outreach is the most suitable beginning for preventing trafficking in the country.

References

[1] United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. New York, 1948. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/UDHR/Documents/UDHR_Translations/eng.pdf.

[2] US State Department. Trafficking in Persons Report. Washington D.C., 2016. https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/258876.pdf.

[3] UNICEF. “Infographic: A Global Look at Human Trafficking.” 2017. Accessed January 20, 2017. https://www.unicefusa.org/stories/infographic-global-human-trafficking-statistics.

[4] The World Bank. “World Development Indicators.” 2017. Accessed January 20, 2017. http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=2&series=NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD.

[5] The Global Slavery Index. “Global Findings 2016.” 2017. Accessed January 20, 2017. http://www.globalslaveryindex.org/findings/.

[6] Trafficking in Persons Report, pg. 224.

[7] Nur.kz. “Рабство в Казахстане.” Accessed January 20, 2017. https://www.nur.kz/tag/rabstvo-v-kazakhstane.html.

[8] Trafficking in Persons Report, pg. 396.

[9] Ibid, 361.

[10] Ibid, 378.

[11] Shestakova, Natalya. “Ежегодно в Кыргызстане фиксируется около 5 тысяч случаев работорговли” [5,000 cases of human trafficking annually in Kyrgyzstan]. Вечерний Бишкек, August 1, 2016. http://www.vb.kg/doc/344269_ejegodno_v_kyrgyzstane_fiksiryetsia_okolo_5_tysiach_slychaev_rabotorgovli.html.

[12] State Migration Service under the Government of the Kyrgyz Republic. Report on Combatting Human Trafficking for 2015. Bishkek, 2015. http://www.mz.gov.kg/reports/view/4.

[13] Sputnik. “Петрушевский: Ребенка в Кыргызстане легче купить, чем усыновить” [Petrushevsky: A child in Kyrgyzstan is easier to buy than adopt]. ru.sputnik.kg, June 25, 2015. http://ru.sputnik.kg/Kyrgyzstan/20150625/1016300478.html.

[14]Sputnik. “По факту продажи ребенка за 25 тыс сомов возбудили уголовное дело” [Criminal case for selling a child for 25,000 soms]. ru.sputnik.kg. June 24, 2015. http://ru.sputnik.kg/incidents/20150624/1016258498.html.

[15] Kabar. Бакыт Эгембердиев: “В Кыргызстане есть точки продажи детей разного возраста” [Bakyt Egemberdiev: “In Kyrgyzstan, there are points for the sale of children of all ages”]. kabar.kg. June 5, 2016. http://www.kabar.kg/rus/society/full/34578.

[16] Delo. “ДЕТЕЙ ПРОДАЛИ НА ОРГАНЫ?” [Children sold for organs?]. delo.kg, January 20, 2016. http://delo.kg/index.php/2011-08-04-18-06-33/9190-detej-prodali-na-organy.

[17] International Organization of Migration. “IOM Bishkek: Counter-Trafficking and Assistance to Migrants in Central Asia.” 2012. Accessed January 20, 2017. http://iom.kg/en/?page_id=116.

[18] Delo. “КТО КОШМАРИТ КЫРГЫЗОВ В МОСКВЕ?” [Who is the nightmare of Kyrgyz in Moscow?]. delo.kg, 2013. http://delo.kg/index.php/2011-08-04-18-06-33/6216-kto-koshmarit-kyrgyzov-v-moskve.

[19] Chushtuk, Aisha. “Бывшие сотрудники МВД Кыргызстана задержаны за торговлю людьми” [Former employees of the Interior Ministry of Kyrgyzstan detained for trafficking]. kyrtag.kg, March 22, 2016. http://kyrtag.kg/society/byvshie-sotrudniki-mvd-kyrgyzstana-zaderzhany-na-torgovlyu-lyudmi-.

[20] Ivashenko, Ekaterina. “Кыргызстан: Рабов становится все больше” [Kyrgyzstan: Slavery is growing]. fergananews.com, January 24, 2014. http://www.fergananews.com/articles/8025.

[21] Justice Ministry of the Kyrgyz Republic. ПРОГРАММА Правительства Кыргызской Республики по борьбе с торговлей людьми в Кыргызской Республике на 2013-2016 годы [Program: Government of the Kyrgyz Republic for Combating Trafficking in Human Beings in the Kyrgyz Republic for 2013-2016]. Bishkek, 2013. http://cbd.minjust.gov.kg/act/view/ru-ru/93915.

[22] Indina, Maria. “Как бороться с торговлей людьми и что делать, чтобы кыргызстанцы не уезжали в Сирию?” [How to deal with human trafficking, and what to do with Kyrgyzstanis who did not leave for Syria?]. knews.kg, November 18, 2016. http://knews.kg/2016/11/kak-borotsya-s-torgovlej-lyudmi-i-chto-delat-chtoby-kyrgyzstantsy-ne-uezzhali-v-siriyu/.

[23] Osmonova, Nargiza. “Для борьбы с торговлей людьми в Кыргызстане предлагают создать координационный совет при правительстве” [To combat trafficking in Kyrgyzstan, the government proposes creating a coordinating council]. 24.kg, February 1, 2016. http://24.kg/vlast/27021_dlya_borbyi_s_torgovley_lyudmi_v_kyirgyizstane_predlagayut_sozdat_koordinatsionnyiy_sovet_pri_pravitelstve_/.

[24] Begalieva, Nazgul. “В Кыргызстане 99 медресе работают без сертификата” [99 madrassas are operating without certification in Kyrgyzstan]. Вечерний Бишкек, July 27, 2016. http://www.vb.kg/doc/344051_v_kyrgyzstane_99_medrese_rabotaut_bez_sertifikata.html.

[25] Kozhobaeva, Zamira. “Число уезжающих в Сирию кыргызстанцев значительно снизилось” [The number of Kyrgyz people leaving for Syria has significantly decreased]. Radio Azzatyk, November 3, 2016. http://rus.azattyk.org/a/28092731.html.

Author: Atai Moldobaev, head of “Prudent Solutions” Analytical Department (Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan).

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the view of cabar.asia.