“An insufficient and poor quality coverage of human trafficking in the regional media is another issue complicating the fight against the threat. For example, some journalists clearly limit themselves to stating that trafficking exists and they do not go beyond that”, – Zaynab Dost, an independent analyst, writes for cabar.asia.

Follow us on LinkedIn!

Problem of defining the scope of the human trafficking

Problem of defining the scope of the human trafficking

Human trafficking is one of the most difficult crimes to prove. In Central Asia, victims of such crimes often do not wish to report their ordeal to the law enforcement agencies. Their mentality does not always allow speaking up about being trafficked or forced into prostitution. This makes an assessment of the threat’s real extent a complicated task. At this point, there is limited data on human trafficking and one can only guess an actual number of the people affected.

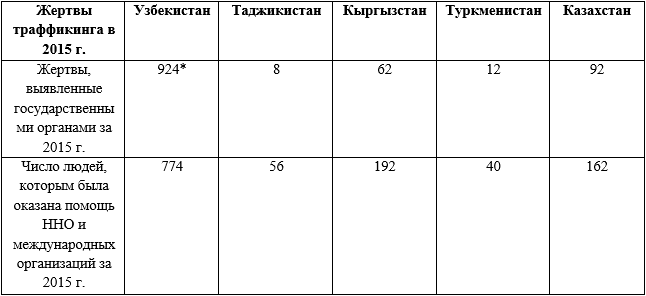

For example, Kazakhstan is reportedly registering about 400 human trafficking cases per year [1]. In Tajikistan, 59 cases were reported in 2015 [2]. The Uzbekistani authorities mentioned 696 investigation processes, 372 criminal cases and 460 people convicted for trafficking humans in 2015 [3]. The Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Republic of Uzbekistan specified that 924 people were trafficked in 2015 and 784 of those were taken out of the country. [4]

There is a difference between the official numbers and independent estimates. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) mentioned 175 trafficking cases in Kyrgyzstan in the first half of 2016. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Kyrgyzstan registered 8 crimes in the same period [5]. Turkmenistani authorities identified 12 victims of human trafficking in 2015 [6], yet an international organization reportedly aided 40 victims of trafficking in the same year. In a similar fashion, the state bodies in Tajikistan identified 8 victims in 2015, however NGOs and international organizations confirmed providing support to 56 victims [7] in the same period of time.

Table 1. Human trafficking victims in Central Asia in 2015

(Based on the US State Department Report on Trafficking in Persons 2016)

*140 of those were exploited in Uzbekistan

*140 of those were exploited in Uzbekistan

Types and routes of the human trafficking in the region

There are two types of trafficking in Central Asia: subjecting people to forced labour and forcing women and children into prostitution.

The sale of Central Asian men as slaves to work in construction and field work is now an established reality. Financial difficulties and unstable income in their home countries drive people to migrate. Some of these individuals end up becoming enslaved. According to a research, men between the age of 18 and 34 with no university or specialized education, residing in the remote areas of Central Asian countries are particularly vulnerable [8]. For example, men from Uzbekistan are forced to work in construction, oil extraction, agriculture, trade and food industries of Russia and Ukraine [9]. The same fate is suffered by other nationals. People from Kyrgyzstan go to Russia for work and some end up being exploited in agriculture, forestry and in textile industry. [10]

In turn, women of Central Asia are vulnerable to sexual exploitation. Women and children from Uzbekistan are forced into prostitution in the Middle East, Eurasia and Asia. In May 2016, the Uzbekistani security services cracked down on a criminal group engaged in trafficking girls to Turkey [11]. In November 2016, police and international organizations freed 17 Uzbekistan born girls – victims of sexual slavery in Malaysia [12].

Unfortunately, not all the women escape safely. At the end of 2015, Indian media reported about two Uzbek dancers – Shahnoza Atabaeva and Shahnoza Shukurova who were murdered in Delhi. The investigation established that Shakhnoza Atabaeva, a native of Khorezm in Uzbekistan, had been promised a job of a housekeeper in India. In reality she was forced into prostitution. Another Shahnoza succumbed to a similar fate, being killed by the same pimp who had lured both girls into trap with the help of his wife’s, a native of Uzbekistan [13].

It’s worth mentioning that human trafficking often occurs within Central Asia itself. Due to its relative prosperity, Kazakhstan is both the country of origin and destination. For example, a young man from Djizzak in Uzbekistan was enslaved after believing a woman who had promised him a monthly 500 US dollars salary for cultivating melons and watermelons in Kazakhstan’s Dzhetisay area. Born in 1993, this young man and his friend were sold to the field owner who took their passports and made them work in inhumane conditions. It was only due to harvesting season’s end and a help of another person, these two Uzbek men could escape to Uzbekistan [14].

According to the estimates, victims of forced labour among the Central Asians prevail over the number of victims of sexual exploitation. The UNODC trafficking figures for 2016 show 63% of the victims as men, 31% women, 4% and 2% of children, male and females, respectively. At the same time, the data varies by country – in 2014 Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan seem to have a higher number of forced labour victims, while Tajikistan has more cases of people trafficked for prostitution [15].

Combating human trafficking

The legislation of the Central Asia countries has all the necessary background to combat trafficking successfully. All Central Asian countries recognize trafficking as a criminal offense and define this crime accordingly. The countries are parties to the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (New York, 15 November 2000). All the countries but Kazakhstan have ratified the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, supplementing the UN Convention above.

In Uzbekistan, the Republican Interdepartmental Commission to Counter Trafficking in Persons coordinates the activities of the state bodies, mahalla (local self-governance entities) and the non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to fight human trafficking. The government of Uzbekistan gives funds to the Tashkent Rehabilitation Center for men, women and children with an official status of a victim. The Center assisted 503 victims in 2015, compared to 369 people in 2014 [16]. The government tries to inform the public about the consequences of human trafficking via setting up information boards, showing films and supporting theatrical plays. Another measure, a rather peculiar one, is to fight human trafficking via demanding all women under 35 years old to get an official permission from their parents or husbands for travelling abroad.

In May 2014, the government of Kazakhstan approved its Plan to Prevent and Fight Trafficking in Persons for 2015-2017. The authorities are working on recognizing the victims of human trafficking and coming up with the criteria to assess ill-treatments leading to a person’s social isolation. This assessment and confirmation of a victim status is supposed to be taking place regardless of whether a criminal case is open or not. [17].

In Tajikistan, the Office for Combating Organized Crime (OCOC), the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and the United States are known for supporting activity of a relatively new Anti-Trafficking Centre. In 2014, the Parliament passed a new law “On combating human trafficking and assisting the victims of trafficking” outlining a harsher punishment for the crime. Similar to Uzbekistan, Tajikistan organizes events to highlight the problem of trafficking, including theatrical performances. [18].

In 2015, Kyrgyzstan’s State Service for Migration developed a draft law on amendments to the law “On Preventing and Combating Trafficking in Persons” in collaboration with international organizations. In addition, the country launched its interdepartmental working group to come up with criteria to identify victims of human trafficking [19].

In 2014, Turkmenistan also set up its working group to combat trafficking. It includes the state representatives and public organizations. The government has also adopted a National Plan to Combat Human Trafficking for 2016-2018, a measure recommended by the international observers in 2015 [20].

Central Asian governments collaborate with the non-governmental organizations and foreign partners to counter human trafficking. They cooperate with the UN representatives, the OSCE, the IOM and UNODC and take part in trafficking prevention and victim protection programs.

Challenges in Combating Human Trafficking

The economic inequality and lack of opportunities for a decent lifestyle is pushing many people to migrate. In Central Asia, like in many post-Soviet countries, success is often associated with migrating abroad or at least finding a temporary job there. In this regard, many inexperienced youth fall into the traps of traffickers who lure the victims by promising them a good income. Analyzing the UNODC data for 2011 – 2014, one sees a direct link between the gross national income per capita, and cross-border trafficking in persons [21].

An insufficient and poor quality coverage of human trafficking in the regional media is another issue complicating the fight against the threat. For example, some journalists clearly limit themselves to stating that trafficking exists and they do not go beyond that. In Kyrgyzstan, about 70% of hardcopy and digital media report the facts alone, while investigative journalism pieces that could have formed a reader’s opinion were rare [22]. The same scenario is observed looking at the media materials of other countries in the region. It is clear that social stereotypes do not always allow people to reveal the real victims stories. However, reporters need to understand that silence can have a negative impact on the public awareness of modern-day slavery. For example, the Uzbekistani media suffer from a self-censorship problem of many journalists and editors, who believe that one needs to report solely positive news.

A distrust of the human trafficking victims felt towards the law enforcement bodies and refusal to ask for help is another challenge in countering the problem. According to the representatives of the OSCE in Tajikistan, people are more likely to turn to non-governmental organizations, rather than police for the first time [23]. The same is observed in other countries for a number of reasons. First of all, a formal recognition of a victim’s status is not a straightforward procedure in Central Asia. A statement of the victim alone is not sufficient. For example, in Kazakhstan recognizing someone as a victim depends on a successful investigation and prosecution. In Kyrgyzstan, it is the same: a law passed, however proving human trafficking is difficult while the Penal Code makes the proof mandatory. In Tajikistan, the NGOs do not play enough role in determining the status of human trafficking victims and they should be allowed to. Second, the lack of legal knowledge and skills related to protecting the rights of the victims often leads to their re-victimization and discrimination. In some cases, people forced into slavery had to pay penalty for crossing the border illegally and were deported. Third, there is corruption among certain law enforcement officials in the region. For example, some Kyrgyzstan police representatives allegedly exploited women – victims of trafficking (including girls younger than 18 years old) and received bribe from traffickers for not launching a criminal case against them [24]. One cannot ignore the fact that trafficking in Central Asia and in the world at large, sadly occurs with the help of corrupt law enforcement and border control authorities. A condemnation of such cases in the media and fight against those is another important step to counter the trafficking in persons.

Recommendations

First of all, it is essential to recognize that raising journalism standards and expanding the media coverage of the issue as a vital necessity in the 21st century. The governments of Central Asia must create conditions for the state and non-state media to highlight the human trafficking threat freely. Investigative journalism and publication of real-life stories following the trails of human trafficking routes could be of greater use for the population as opposed to plain reports on human trafficking facts. The NGOs must be given more opportunities to publish their reports and evaluations in the regional media outlets. In Uzbekistan, human trafficking is indeed covered in special programs broadcasted on TV and radio, and internet portals. For example, the Department for Countering Human Trafficking and Missing Persons of the Ministry of Internal Affairs had been publishing a series on real human trafficking cases in 2015 [25]. However, journalists could supplement the law enforcement agencies information by special reports with a greater emphasis on the human story. In addition, information boards and leaflets warning against human trafficking must be present in all international airports, train stations and border crossings of Central Asian countries. The importance of digital media should be also taken into account given its popularity among the young users. In 2014, there was a practice of sending text messages warning against human trafficking by mobile operators across Uzbekistan [26]. Given the popularity of social media, the law enforcement bodies could distribute information through mobile apps like Viber, Telegram, Imo, and social networks like Facebook and Odnoklassniki.

Second, the current preventive measures in Central Asia are mainly aimed at holding special trainings and giving public speeches at the universities or specialized education institutions. Given that victims of human trafficking are often people without education (although there may be exceptions), prevention should target informing people starting from their highschools. The governments of Central Asia together with the assistance of psychologists, NGOs, law enforcement agencies and international partners could launch a program of recurrent trainings at schools warning the younger generation against the dangers of an illegal work abroad. Trainings could include real stories of human trafficking victims and be based on the human rights and dignity protection enshrined in the constitutions of Central Asian states. Moreover, the program could warn against tricks and methods used by traffickers, highlighting the fact that relatives and acquaintances can be traffickers too. Accordingly, it is imperative to normalize a practice of a thorough check of any information about a potential job offer abroad via the middle men. As a rule, no legitimate business would hire foreign employees without relevant paperwork.

Third, it’s necessary to establish a single regional digital database to track crimes related to human trafficking. As trafficking in persons occurs within the region, its law enforcement bodies need to have a constant exchange of information to coordinate their activities. Such a database could be launched by a direct government support with assistance from international donors. It can be founded as an independent project or it can be implemented within existing analytical centres of information. Bearing in mind the link of trafficking to other organized crime forms, such as terrorism and drug trafficking, it could be possible to create such a database within the Central Asian Regional Information and Coordination Centre for combating illicit drug trafficking (CARICC). Another option is to develop the project within operating anti-terrorist bodies in the view of terrorist organizations’ links to human trafficking. It is known that the so-called “Islamic State” organizes markets selling women and children. Recently, international organizations reported about Kyrgyzstani citizens who had joined the militants of the “IS” and have been held with them against their will [27]. The launch of such an information resource and open access to could enable journalists to write stories on how terrorist and trafficking groups perceive people as a commodity to be exploited for political and commercial ends.

Fourth, there is a need for greater coordination in monitoring and restricting criminal organizations involved in human trafficking in Russia, Kazakhstan, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. Joint and regular cooperation of the law enforcement authorities of respective countries is highly required and so are their recommendations for the executive branches of power. Suppressing the demand for humans in the countries of destination would bring a drop in supply in the countries of origin.

Finally, it is important to create jobs and practice economic freedoms with a compulsory diversification of the Central Asian economies. Opportunities for entrepreneurs and a departure from the resource-based economies is a massive task for the countries of the region. In this respect, the government efforts must be united with those of NGOs, media, academia, public figures and donor organizations.

Sources:

[1] S. Baybusinov “In Kazakhstan 400 human trafficking cases are registered”, 07.10.2016, http://khabar.kz/ru/news/obshchestvo/item/65730-v-kazakhstane-ezhegodno-registriruyut-do-400-faktov-torgovli-lyudmi

[2] “IWPR Tajikistan: Export and trafficking in persons for exploitation is becoming a long-term problem in Tajikistan”, 03.02.2016, http://analytics.cabar.asia/ru/iwpr-tajikistan-vyvoz-i-torgovlya-lyudmi-s-tselyu-ekspluatatsii-prevrashchayutsya-v-tadzhikistane-v-dolgosrochnoe-yavlenie/

[3]US Department of State Trafficking in Persons Report 2016, https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/258876.pdf; p.396

[4] Sputnik “The number of slave trade victims from Uzbekistan is down by 23,5% in 2015”, 18.07.16, http://ru.sputniknews-uz.com/society/20160718/3355161.html

[5] REGNUM, “There is no single account of human trafficking victims in Kyrgyzstan” ,16.12.2016, https://regnum.ru/news/society/2218693.html

[6] Alternative news of Turkmenistan, “The US Department of State downgrades Turkmenistan’s tier in its report on trafficking in persons”, 30.06.16, https://habartm.org/archives/5281, 30.06.2016

[7] US Department of State Trafficking in Persons Report 2016, https://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/countries/2016/258874.htm

[8] Report of SIAR Research & Consulting “Identification of rehabilitation and reintegration needs of men, victims of human trafficking”, 2015, prepared for the International Organisation of Migration, http://iom.kg/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Needs-of-male-VOT-Rus.pdf

[9] The US Embassy in Uzbekistan: “Report on trafficking in persons for 2016: Uzbekistan”, https://uz.usembassy.gov/ru/our-relationship-ru/official-reports-ru/2016-trafficking-persons-report-uzbekistan-ru/

[10] Sputnik “The US State Department report – Republic of Kyrgyzstan is a source for human trafficking into Russian and Kazakhstan”, 29.07.15, http://ru.sputnik.kg/society/20150729/1017037229.html

[11] Sputnik “Members of an organised crime group trafficking women girls to Turkey are arrested in Uzbekistan”, 23.05.2016, http://ru.sputniknews-uz.com/incidents/20160523/2870080.html

[12] Centr-1 “Uzbekistani women tell how they were enslaved and survived”, 21.11.16, https://centre1.com/uzbekistan/uzbekistanki-rasskazali-kak-ugodili-v-rabstvo-i-vyzhili/

[13] Daily News and Analysis, “From taxi rides to forced prostitution: How foreigners in India are being trapped by human traffickers”, 21.11.2015, http://www.dnaindia.com/delhi/report-from-taxi-rides-to-forced-prostitution-how-foreigners-in-india-are-being-trapped-by-human-traffickers-2147472

[14] Report of SIAR Research & Consulting “Identification of rehabilitation and reintegration needs of men, victims of human trafficking”, p.27, 2015, prepared for the International Organisation of Migration, http://iom.kg/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Needs-of-male-VOT-Rus.pdf

[15] UNODC Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2016, http://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/glotip/2016_Global_Report_on_Trafficking_in_Persons.pdf

[16] The US Embassy in Uzbekistan: “Report on trafficking in persons for 2016: Uzbekistan”, https://uz.usembassy.gov/ru/our-relationship-ru/official-reports-ru/2016-trafficking-persons-report-uzbekistan-ru/

[17] Media center of Ministry of Internal Affairs of Kazakhstan, “Human trafficking – legal aspects”, 25.02.16,http://mediaovd.kz/ru/?p=7696

[18] Asia-Plus “IOM Tajikistan brings threats of human trafficking into theatre scene”, 20.05.2015, https://news.tj/en/news/tajikistan/society/20160520/iom-tajikistan-brings-threats-human-trafficking-theatre-scene

[19] REGNUM, “There is no single account of human trafficking victims in Kyrgyzstan”, 16.12.2016, https://regnum.ru/news/society/2218693.html

[20] Huseyn Hasanov “Turkmenistan approves national plan to fight human trafficking”, 30.05.2016, http://en.trend.az/casia/turkmenistan/2539805.html

[21] UNODC Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2016, http://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/glotip/2016_Global_Report_on_Trafficking_in_Persons.pdf

[22] Collection of materials for Report on Counter Trafficking in persons: Central Asia / Protection of human rights for the victims of trafficking in persons and vulnerable groups in Central Asia: 2012-2015”, p.17, http://www.osce.org/ru/odihr/180256?download=true

[23] OSCE “Shining a light on trafficking in human beings in Tajikistan”, 26.06.2015, http://www.osce.org/tajikistan/166981

[24] US Department of State Trafficking in Persons Report 2016, https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/258876.pdf ; c.235

[25] Uzbekistan News “Warning! Human sale”, 10.02.2016, http://nuz.uz/trudovaya-migraciya/10971-ostorozhno-prodazha-lyudey-chast-1.html

[26] Statement of Bahodir Abduvaliev, Acting Deputy Department Head of the General Prosecutor of the Republic of Uzbekistan at the OSCE Human Dimension Implementation Meeting (22 September-3 October 2014, Warsaw), http://www.osce.org/ru/odihr/124292?download=true

[27] US Department of State Trafficking in Persons Report 2016, https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/258876.pdf

Аuthor: Zaynab Dost, independent analyst (London, UK)

The position of the author does not necessarily reflect the position of the cabar.asia